Richard Haass told CNA that Washington’s China policy has appeared inconsistent, pointing to mixed signals from the administration.

US President Donald Trump and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping meet in Busan on Oct 30, 2025. (Photo: AFP/Andrew Caballero-Reynolds)

New: You can now listen to articles.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

The United States’ approach to China and the Indo Pacific remains “the biggest area of uncertainty” in President Donald Trump’s foreign policy – even as Washington and Beijing maintain contact ahead of a crucial leaders’ meeting later this year, said veteran American diplomat Richard Haass.

He downplayed the significance of a phone call on Wednesday (Feb 4) between Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping, which took place just hours after Xi held a video chat with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

During the call – their first since November – Xi and Trump discussed Taiwan, as well as a range of trade and security issues that continue to fuel tensions between the world’s two largest economies.

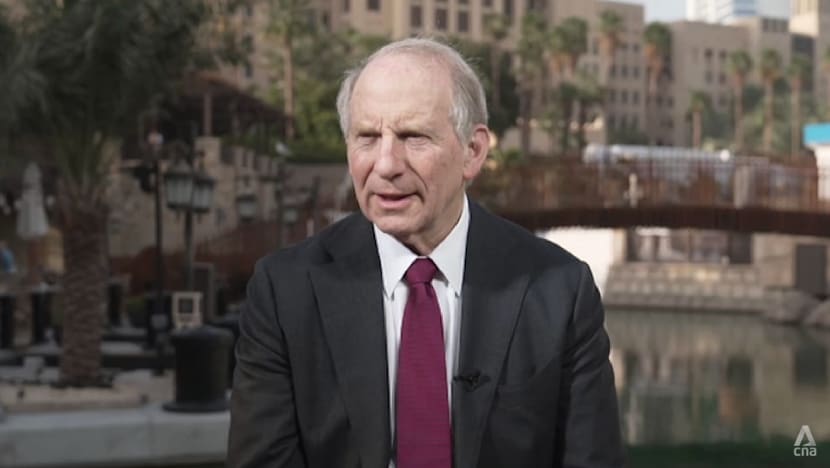

“Everyone's going to be trying to read everything they can into the phone call,” Haass, president emeritus of American think-tank Council on Foreign Relations, told CNA on Thursday.

“Obviously, the US and China have very different priorities. But I don't think the phone call itself changed much, if anything.”

He was speaking on the sidelines of the World Governments Summit in Dubai, which comes at a time of rising geopolitical tensions. The annual event brings together leaders from government, international organisations and the private sector to promote cooperation on future challenges.

Richard Haass, president emeritus of American think-tank Council on Foreign Relations, speaking to CNA on the sidelines of the World Governments Summit in Dubai.

Richard Haass, president emeritus of American think-tank Council on Foreign Relations, speaking to CNA on the sidelines of the World Governments Summit in Dubai.

MIXED SIGNALS ON CHINA

China and the US are seeking areas of common ground ahead of the anticipated April meeting between Trump and Xi in Beijing.

Haass said Washington’s China policy has appeared inconsistent, pointing to mixed signals from the administration.

On one hand, the US last December announced its largest-ever arms sales package to Taiwan, valued at more than US$11.1 billion – a move that has rattled Beijing. On the other hand, it has eased its stance on some areas in recent months, including on tariffs and advanced chips.

“It's very hard to read a consistent direction in the US approach to China,” said Haass, adding that many are hoping the April meeting will clarify whether Washington intends to prioritise commerce or strategic competition with Beijing

“It's why this meeting in April is so important, because people are thinking, or at least hoping, that we finally get a degree of clarity and consistency.”

In particular, Haass pointed to uncertainty over how far the US is prepared to go on Taiwan, which China views as its own territory. “That remains a big question,” he said.

Taiwan President Lai Ching-te said on Thursday that relations with the US are "rock solid", and cooperation programmes will continue and not change despite the Trump-Xi call.

Haass argued that Washington should move away from its policy of “strategic ambiguity” towards the self-ruled island.

“I think the United States should move to a position of strategic clarity that we will come to Taiwan's aid if the mainland used force against it,” he said.

“At the end of the day, foreign policy is not just about will, it's also about capability,” he added.

“We need to marry the two, and that's where I believe strategic clarity backed up by greater capability would be very much consistent with promoting the stability of this critical part of the world.”

RETHINKING RULES-BASED ORDER

At the same time, countries are increasingly adjusting to a world in which Washington is no longer seen as the central guarantor of global security.

Haass cited a speech by Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney at last month’s World Economic Forum in Davos, urging middle powers to work together to counter the rise of hard power. Carney also warned that the US-led global system of governance was facing a “rupture”.

“It was a recognition on his part, almost a public declaration, that medium countries that have long been allies to the United States can no longer place the bulk of their security in American hands. They also need to be wary about getting too close to (the US) economically, because we could use that for leverage,” he said.

“What the Canadian prime minister said is what a lot of national security advisors and ministers and the like are saying privately and he just said it publicly, that this is a different world.

“It's not that the United States has disappeared from their calculations, it's just not as central or as prominent, and they have to adjust to that.”