Jakarta wants to take its bridge-building diplomacy from ASEAN to North Korea, says researcher Akhmad Hanan.

Indonesian Foreign Minister Sugiono (left) and North Korean Foreign Minister Choe Son Hui, in Pyongyang, Oct 11, 2025. (Photo: X/Menlu_RI)

JAKARTA: Indonesia’s decision to renew diplomatic engagement with North Korea this month is more than a nostalgic gesture recalling the Sukarno–Kim Il Sung era. Foreign Minister Sugiono’s visit to Pyongyang on Saturday (Oct 11), at the invitation of North Korean Foreign Minister Choe Son Hui, marked a new phase in Indonesia’s quiet but deliberate diplomacy.

At a time when China, Russia and North Korea are forging a closer axis of cooperation, Indonesia is positioning itself as a middle power capable of engaging all sides without compromising its independence.

This first trip by an Indonesian foreign minister to North Korea since 2013 saw a renewed Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) for a bilateral consultation mechanism, which Indonesia’s foreign ministry has described as a platform to explore cooperation across political, socio-cultural, technical and sports sectors.

Sugiono affirmed Jakarta’s readiness to facilitate closer engagement between North Korea and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), including through mechanisms such as the ASEAN Regional Forum. The minister also attended the 80th anniversary celebration of the Workers’ Party of Korea, a symbolic gesture underscoring respect for an old partner and Indonesia’s quiet ambition to act as a diplomatic bridge amid Pyongyang’s isolation.

The relationship between Jakarta and Pyongyang, rooted in the spirit of the Bandung Conference and the Non-Aligned Movement, never collapsed even during decades of global tension. The two nations first established diplomatic relations in the 1960s. Yet the renewed MOU now takes on new resonance in an era of sharpened rivalry and shifting power balances across East Asia.

REALISM, NOT IDEOLOGY

Jakarta continues to maintain defence cooperation with the United States and Australia while deepening economic and technological ties with China. By reopening communication with Pyongyang, Indonesia signals that it can speak to all parties without asking permission from any.

This initiative also reflects Jakarta’s longstanding aspiration to act as a regional mediator. By encouraging North Korea’s participation in ASEAN-led forums, Indonesia is reviving its traditional role as a bridge-builder, a hallmark of its “bebas aktif” (independent and active) foreign policy doctrine.

Indonesia’s move intersects with China’s own efforts to normalise Pyongyang’s regional presence. Following Kim Jong Un’s attendance at Beijing’s military parade last month, China appears keen to promote North Korea’s limited reintegration into regional diplomacy.

Jakarta’s initiative complements this effort in a uniquely Southeast Asian way: soft, non-confrontational, and rooted in dialogue rather than deterrence.

Prabowo’s brand of diplomacy is grounded in realism rather than ideology. He sees foreign policy as an instrument of sovereignty and interests, not as a field for value-driven alignment.

Economically, the relationship between Indonesia and North Korea remains minimal, yet carries symbolic weight. Jakarta’s engagement reinforces its image as a dialogue-oriented actor in an increasingly divided region, one willing to talk where others prefer to isolate. Discussions between the two nations on agriculture, technology and sports cooperation are politically neutral but diplomatically significant. They underscore Indonesia’s desire to build bridges rather than walls.

While many countries are pressured to choose sides between Washington and Beijing, Jakarta continues to pursue its own path, strengthening ASEAN’s centrality while keeping constructive ties with all major powers, from the United States to North Korea.

PERCEPTION CAN BE AS POWERFUL AS POLICY

Still, this approach is not without risk. Any attempt to deepen cooperation with Pyongyang must remain compliant with United Nations sanctions, a line Jakarta is careful not to cross.

Indonesian officials have repeatedly stressed that the engagement focuses solely on humanitarian, socio-cultural and technical cooperation, not on military or financial collaboration.

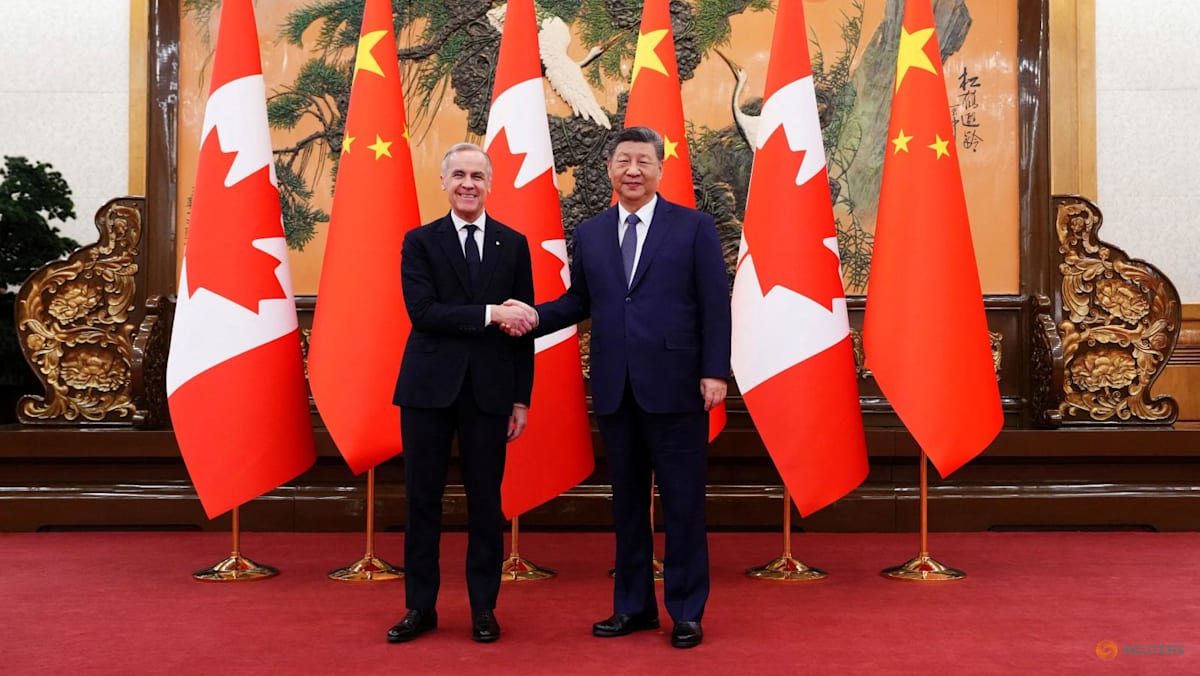

Yet perception can be as powerful as policy. The image of Prabowo himself standing beside Chinese President Xi Jinping, Russian President Vladimir Putin, and Kim during the recent military parade in Beijing, followed by the foreign minister’s visit to Pyongyang, may fuel speculation that Indonesia is drifting toward the Eurasian bloc.

Such interpretations, however, overlook Jakarta’s fundamental diplomatic instinct: to maintain equal distance from all major powers while maximising its interests.

Much like its industrial partnerships with Chinese electric vehicle giants such as BYD and CATL, Jakarta’s diplomacy reflects a pragmatic effort to draw benefits from all sides without surrendering control.

The visit to Pyongyang will not transform the Korean Peninsula overnight, but it underscores a conviction that engagement, especially from middle powers, can still carve out space for diplomacy in an era of confrontation. Whether this quiet diplomacy succeeds will depend on Jakarta’s ability to balance symbolism with substance.

But one thing is clear: for Indonesia, the true measure of sovereignty lies not in choosing sides, but in maintaining the freedom to speak with all.

Akhmad Hanan is an independent Indonesian researcher specialising in geopolitics and energy. This commentary first appeared on the Lowy Institute's blog, Interpreter.