Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul’s political strategy paid off, but his victory was also due to a fortunate combination of circumstances, says Harrison Cheng from Control Risks.

A woman casts her vote during early voting day on Feb 1, 2026, in Bangkok ahead of the general election on Feb 8, 2026. (Photo: CNA/Zamzahuri Abas)

New: You can now listen to articles.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Political stability has eluded Thailand for more than a decade. But on Sunday (Feb 8), the country’s general election offered a glimpse of it for the first time in a long while.

Led by Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul, the conservative Bhumjaithai (BJT) Party stormed its way to victory. It is on track to win the most seats and expected to be within touching distance of 200 seats in the 500-member lower house.

Trailing the BJT are two parties likely to be deeply disappointed with their performance. The main opposition People’s Party (PP) is expected to take 118 seats, a far cry from the 151 seats secured by its predecessor Move Forward Party in 2023, and a surprise given that the youthful, reformist party had led in pre-election opinion polls.

If the PP’s result is a stumble, Pheu Thai’s can be likened to a fall off the precipice.

Former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra’s party had marked its electoral debut in 2011 by winning a stunning 265 lower house seats but is now expected to control only 76 seats. Controversies have cost the party two prime ministers in the last three years, and with Thaksin currently behind bars for corruption, the party is staring at terminal decline.

That an old-school conservative party, which never placed higher than third in a general election, triumphed is a major shift in Thai politics.

TRIUMPH OF THE CONSERVATIVES

The BJT’s victory is remarkable for at least two reasons. First, the BJT’s estimated 193 seats is a massive improvement from its last electoral outing, a 173 per cent jump from 71 seats in 2023.

One would have to go as far back as 2011 to find a single political party that won 200 or more seats – and that was Pheu Thai. Up until polling day, political parties had struggled to replicate that level of parliamentary muscle. This was due to the disruption introduced by the 2014 military coup and its legacy of electoral and constitutional reforms that fostered parliamentary fragmentation.

Second, the BJT’s sizeable win shows that it is possible to buck the trend of political splintering.

While its core strategy of consolidating power at the local level through alliances with powerful political families (baan yai) has paid off, its victory was largely due to a fortunate combination of circumstances rather than deliberate design.

LEANING ON NATIONAL SECURITY

The BJT could not have predicted the about-face in Thai-Cambodian relations in mid-2025 over a leaked phone call between Thailand’s then Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra and Cambodian Senate President Hun Sen, and the consequent flare-up of their decades-old, simmering border conflict.

Neither could the BJT have expected that its audacious bid to replace Pheu Thai as the leading party in a new government in September 2025 would succeed. Surely the PP, which holds diametrically opposite views to the BJT, would not lend their support to Mr Anutin as prime minister? And yet it did.

But victory appears to be less about having the perfect hand, and more about playing perfectly the cards you have.

The BJT has made full use of the border conflict to amplify its national security credentials. It took advantage of Pheu Thai’s mishandling of the issue and the PP’s reputation for criticising the military, which is still a powerful institution and has enjoyed a surge in public support amid the border conflict.

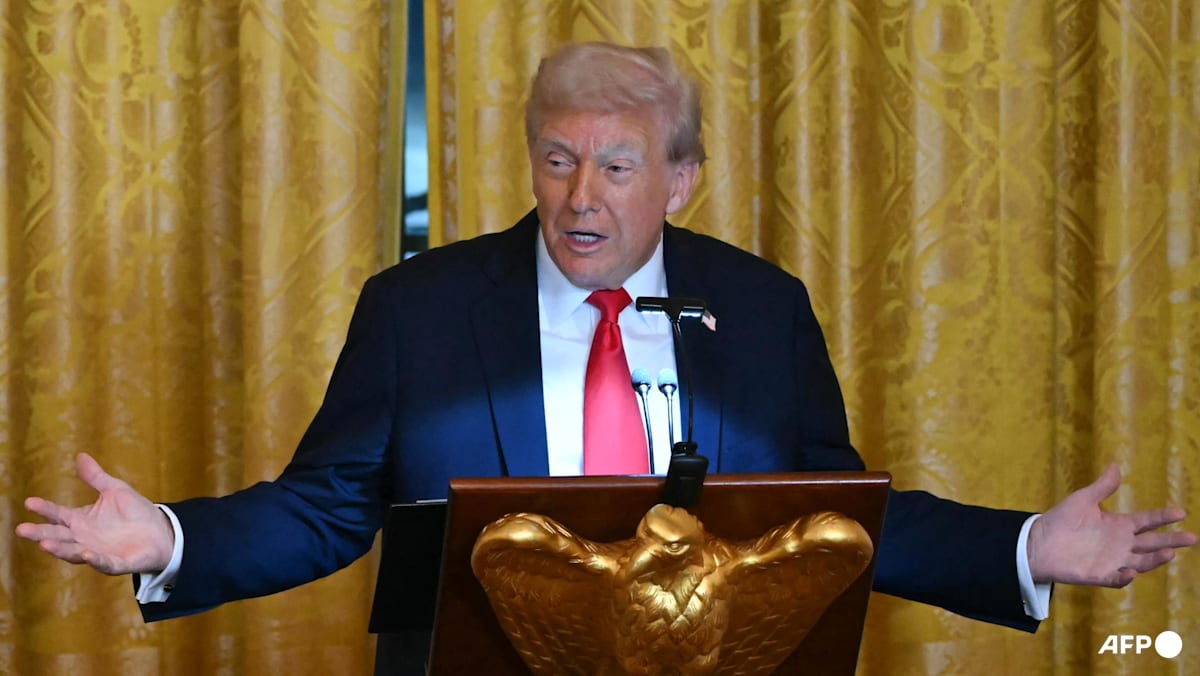

Thailand's caretaker Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul, Bhumjaithai Party leader and prime ministerial candidate, gestures following a press conference at the party headquarters on the day of the general election, in Bangkok, Thailand, Feb 8, 2026. REUTERS/Chalinee Thirasupa

Thailand's caretaker Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul, Bhumjaithai Party leader and prime ministerial candidate, gestures following a press conference at the party headquarters on the day of the general election, in Bangkok, Thailand, Feb 8, 2026. REUTERS/Chalinee Thirasupa

The deal that the BJT struck with the PP also largely benefited itself, allowing Mr Anutin to prove himself as prime minister for four months. The PP will look back at the deal and wonder how much it hurt the party’s ideological appeal amid perceptions that it had opted for compromise over principles.

NOT BEHOLDEN TO PHEU THAI OR PEOPLE’S PARTY

What is most likely to happen next is the emergence of a coalition government comprising BJT and fellow conservative party Klatham. The latter’s strong showing is expected to result in 57 seats.

Mr Anutin would then have the simple majority (251 seats) needed to be re-elected as prime minister. Crucially, he would no longer need the PP or Pheu Thai to stay in power.

A BJT-Klatham government would have significant freedom in advancing its policy and political goals, as it would not be obliged to meet the PP or Pheu Thai’s demands in exchange for their support. While the PP could threaten to withdraw support for Mr Anutin to get its way pre-election, such tactics would no longer be effective.

Even though he does not strictly need Pheu Thai’s numbers, Mr Anutin may well consider luring it into a partnership to bolster his parliamentary position. Such an alliance would control nearly 330 seats – a formidable majority that can be leveraged to accelerate policy pledges, regulatory reforms and ambitious projects.

While the BJT and Pheu Thai have had a contentious relationship, they are remarkably similar in terms of ideological flexibility. But unlike the last time both parties were worked together (from 2023 to 2025), the BJT is now no longer a junior coalition partner but the one who calls the shots.

RESPITE FROM TURBULENCE

The incoming administration is likely to be more stable than its predecessors, which will give both the Thai public and foreign investors a much-needed dose of comfort following years of turbulence.

Mr Anutin’s primary focus will be on the economy, and all eyes will be on his technocratic team to deliver on their promises. Households will want solutions to chronic indebtedness which has inhibited spending, and businesses are chomping at the bit for regulatory streamlining and clear, long-term sectoral growth policies that will incentivise foreign investment and encourage the development of Thai supply chains.

This is a golden opportunity for Thailand to shake off the yoke of political turmoil and its reputation as the “sick man” of Southeast Asia that has plagued it for more than a decade.

Thailand will hope that Mr Anutin is the real deal, not a raw deal.

Harrison Cheng is a Director in risk consultancy firm Control Risks.

.jpg?itok=lJgtroiy)