Arthur Lim still speaks about his mother in the present tense. “She uses a bit more of lemongrass,” he said, describing how Alice Choo's laksa differs from traditional versions. For a moment, you forget that Alice passed away in 2019 at age 94, her mind sharp until the end. Yet, her memory lives so vividly in Lim’s kitchen that she might as well be standing beside him, approving each dish with the exacting standards that once made him nervous as a young cook seeking her blessing.

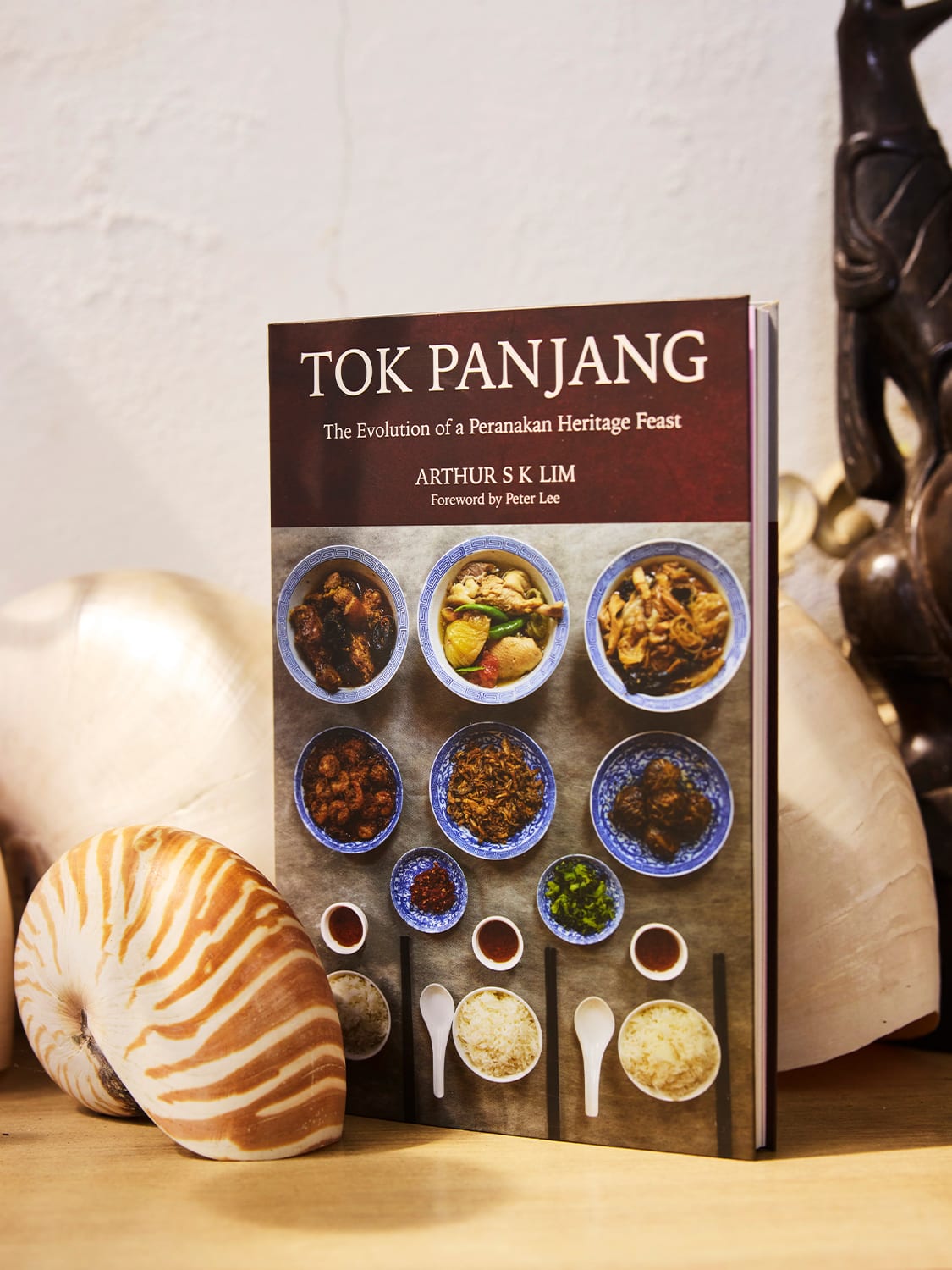

It’s this vivid presence that has driven Lim to an unexpected calling that weaves together his mother's culinary legacy with his own journey as a private dining host. His cookbook Tok Panjang: The Evolution of a Peranakan Heritage Feast, first published in late 2023 by Landmark Books Singapore, represents more than a collection of recipes – it’s the culmination of years spent preserving a disappearing tradition while building his own reputation among Singapore’s most discerning food enthusiasts. The first edition sold out its thousand-copy print run in 18 months, and a second print run has just been released.

The path to this preservation mission was hardly direct. After a long career in finance at OCBC and Standard Chartered Merchant Bank, plus managing a Japanese supermarket in London, Lim returned to Singapore in 2000 expecting a quieter chapter. What he found instead was a calling that had been quietly brewing in his mother’s kitchen all along.

Arthur Lim's cookbook Tok Panjang: The Evolution of a Peranakan Heritage Feast was first published in late 2023. (Photo: Kelvin Chia/CNA)

Arthur Lim's cookbook Tok Panjang: The Evolution of a Peranakan Heritage Feast was first published in late 2023. (Photo: Kelvin Chia/CNA)

For Alice Choo was no ordinary Peranakan cook. As a fifth-generation Baba, Lim traces both sides of his family to Penang and Melaka, but Choo’s lineage was particularly complex, weaving Vietnamese and Thai into the Malaysian influences. Having learned her craft from her own mother, Choo marinated all these influences into something distinctly her own. The Penang heritage brought heavier use of lemongrass and blue ginger to her cooking. The Melaccan tradition contributed more onions and sweetness. Which explains why Choo’s versions were a little sweeter and more sour than typical Peranakan dishes.

Lim began learning at her side when he was 12, his palate slowly trained to understand not just flavours but the precise ratios that made his mother’s food singular. Like Choo, he learned to cook by sight, sound, and smell – watching for the exact colour of cooking meat, listening for the volume of a bubbling stew, waiting for that moment when the fragrance of frying rempah turned just so.

Yet for all this technical virtuoso, neither of them considered this food particularly special. This was simply the repast of their daily lives, nothing more remarkable than breathing.

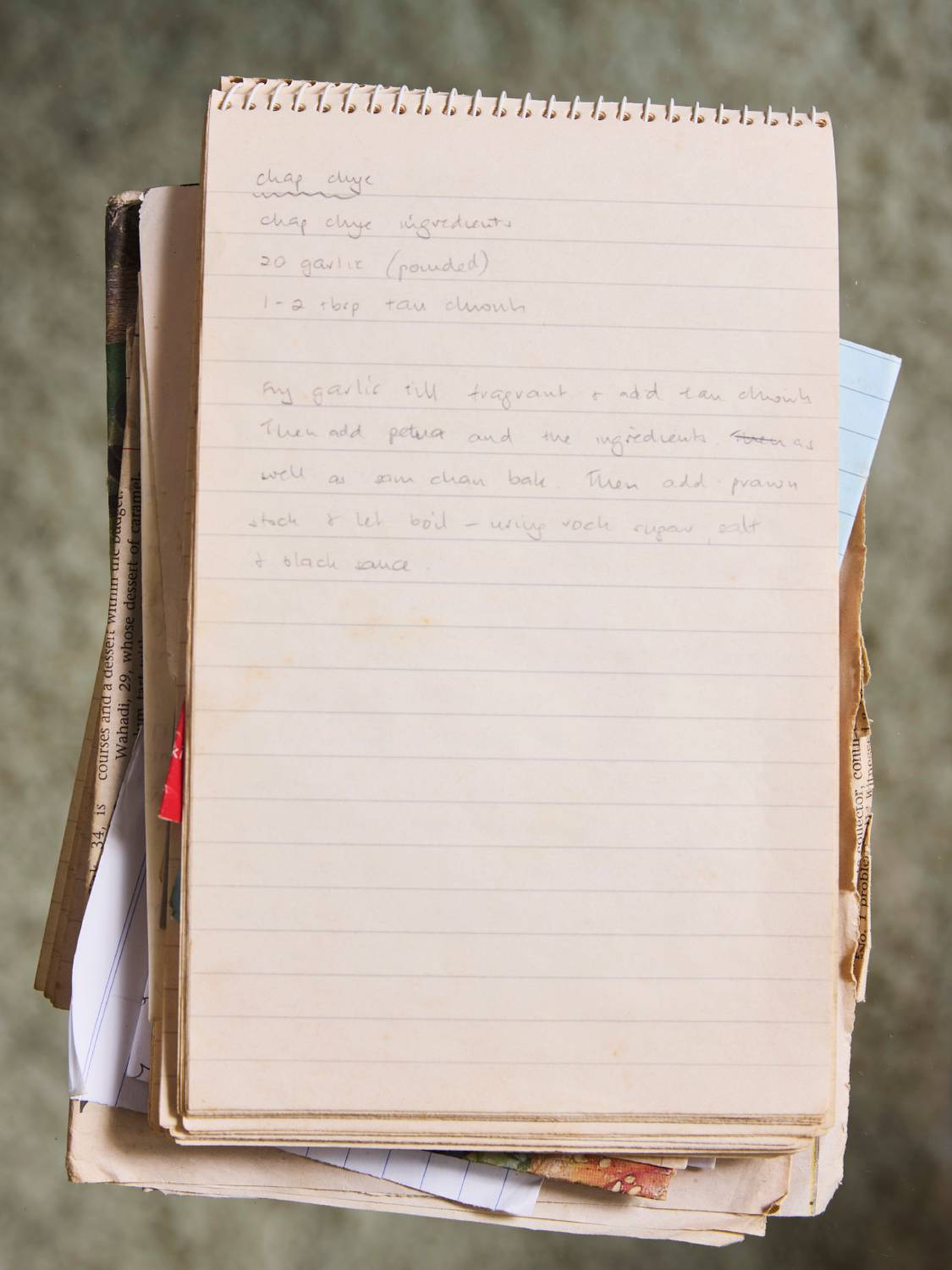

So much so that the preservation of Choo’s repertoire began almost by accident, years later when Lim lived in London. During Choo’s visits, mother and son would find themselves at the kitchen table, chatting over tea, and she would rattle off recipes from memory while Lim, almost absent-mindedly, began jotting them down on scraps of paper. It was painstaking deductive work. Recipes called for “20 cents of grated coconut”, say, or required the rempah to be fried till fragrant, with no further elaboration.

A handwritten Chap Chye recipe from Arthur Lim's mother. (Photo: Kelvin Chia/CNA)

A handwritten Chap Chye recipe from Arthur Lim's mother. (Photo: Kelvin Chia/CNA)

Chap Chye made by Arthur Lim from his mother's recipe. (Photo: Arthur Lim)

Chap Chye made by Arthur Lim from his mother's recipe. (Photo: Arthur Lim)

What started as casual notetaking became something more profound when Lim realised he had accumulated a culinary treasure trove. Back in Singapore, he began hosting dinners at his Joo Chiat home for friends and family.

The revelation came through the gratifyingly positive reactions of others even as word spread among Singapore’s food-conscious circles, leading to increasingly exclusive gatherings for seasoned epicureans who travelled the world eating at Michelin-starred restaurants as a matter of course. Many even encouraged him to share his mother’s recipes more widely. Lim was reluctant. Like Choo, he considered this everyday food, nothing particularly special. “This is just what I grew up eating,” he explained.

One pivotal evening, when Lim was called into his dining room after service, guests spontaneously applauded. The feedback was overwhelmingly enthusiastic. “People would say, ‘I don't like rendang, but why is yours so different?’” he recalled. Another guest couldn’t stop eating something she’d never encountered before, despite years of eating Peranakan food elsewhere. “There were many dishes there that they've never had,” Lim realised.

What started as casual notetaking became something more profound when Arthur Lim realised he had accumulated a culinary treasure trove. (Photo: Kelvin Chia/CNA)

What started as casual notetaking became something more profound when Arthur Lim realised he had accumulated a culinary treasure trove. (Photo: Kelvin Chia/CNA)

But more than anything, he began to understand his mother’s recipes weren’t just family comfort food. They represented something genuinely unique in the Peranakan culinary landscape.

Two years ago, that realisation was transformed into a 128-page cookbook. No larger than a slim paperback, the volume punches above its weight category, its 25 recipes framed against the story of a dyed-in-the-wool Peranakan family and their distinctive culinary traditions. While familiar dishes like babi assam (belly pork braised in tamarind) and udang masak nanas (prawns cooked with pineapple) make their appearance, the cookbook’s real value lies in showcasing recipes that have all but vanished from contemporary Peranakan kitchens.

Lim estimates there are hundreds more recipes for daily dishes, material that could well form the basis of future cookbooks. (Photo: Kelvin Chia/CNA)

Lim estimates there are hundreds more recipes for daily dishes, material that could well form the basis of future cookbooks. (Photo: Kelvin Chia/CNA)

Here you’ll find hati babi bungkus (liver and pork balls wrapped in pig's caul), tee hee (stir-fried pig's lungs), and kuah lada (a peppery stew of Spanish mackerel steaks) – dishes that signal to seasoned Peranakans that this represents a kitchen of altogether different standards. These are the recipes you can’t find for love or money today, except in family kitchens like Lim’s.

Today, Lim's monthly tok panjang dinners have become legendary among those fortunate enough to snag a slot. The term tok panjang – “tok” meaning table in Hokkien, “Panjang” meaning long in Malay – refers to the traditional Peranakan communal feast. The practice can be traced to the long table placed in front of family altars in Peranakan homes, where lauk sembahyang (prayer food) was offered during rituals. After ceremonies concluded, the same food would be consumed by attending family members, transforming sacred offerings into communal celebration.

Lim’s elaborate feasts of a dozen or so dishes, each requiring the kind of meticulous preparation that makes more frequent hosting impractical.

Arthur Lim and his mother. (Photo: Kelvin Chia/CNA)

Arthur Lim and his mother. (Photo: Kelvin Chia/CNA)

But what drives Lim isn’t nostalgia but urgency. As the youngest of 10 children, he was the one most often in Choo’s kitchen, the one whose palate she trained and whose cooking earned her approval. “After me, there will not be continuity,” he said matter-of-factly even as he casually mentions that the 25 recipes in his book represent only a fraction of Choo’s repertoire. He estimates there are hundreds more recipes for daily dishes, material that could well form the basis of future cookbooks.

When asked what his mother would think of the book, Lim’s face brightens with the same expression he describes seeing on hers when guests enjoyed her cooking. “The biggest form of appreciation for her is if you truly get pleasure out of her cooking, or even if it was someone else preparing her dishes. You can literally see the light on her face.”

Today, Lim continues his mother’s tradition of abundance and variety. In preserving her recipes, he has also preserved something else more essential – the warmth and generosity that made Alice Choo's table a place where food became love, and where tradition is finding its way safely into the future.

And perhaps, in some way, she’s still there in that Joo Chiat kitchen, watching approvingly as her youngest son carries forward everything she taught him, her presence as vivid and enduring as the flavours she perfected over a lifetime of cooking.

Tok Panjang: The Evolution of a Peranakan Heritage Feast is available for $29. Contact bentok69a [at] gmail.com for orders.