Concerns about a global trade war have faded, but President Donald Trump’s tariffs will eventually come at a cost to the United States, says Kevin Chen from the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies.

File photo. US President Donald Trump listens during a news conference with India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi in the East Room of the White House, Feb 13, 2025, in Washington. (Photo: AP/Alex Brandon)

New: You can now listen to articles.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: What do a border conflict between Cambodia and Thailand, a former Brazilian president’s trial over an attempted coup and deportation flights to Colombia have in common? In earlier times, probably nothing.

But in this new political era, the answer is simple: United States President Donald Trump has threatened tariffs to force US partners to accede to his demands on these issues.

On Saturday (Jul 26), just days before his Aug 1 tariff deadline, Mr Trump announced on Truth Social that he had spoken to Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Manet and was about to call acting Thai Prime Minister Phumtham Wechayachai, warning them that the US “[did] not want to make any deal, with either country, if they are fighting".

The two Southeast Asian nations agreed to an immediate and unconditional ceasefire on Monday, after talks mediated by ASEAN chair Malaysia.

It’s hard to say if Mr Trump’s warning was heeded. However, the incident does highlight an important truth: To Mr Trump, tariffs are one of the most powerful tools in the US foreign policy arsenal, and it is important to weaponise them instead of siloing trade off from non-economic goals.

This gamble appears to be paying off – to an extent.

THE NEW COST OF DOING BUSINESS WITH AMERICA

Instead of retaliating, countries have chosen to pursue trade deals by offering favourable terms for Washington. The United Kingdom, Japan, Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines, the European Union and South Korea have already reached some sort of deal.

Analysts had earlier warned that Mr Trump’s plans would draw counter-tariffs that could plunge the world into a disastrous trade war. And for a while, that retaliation appeared to be underway.

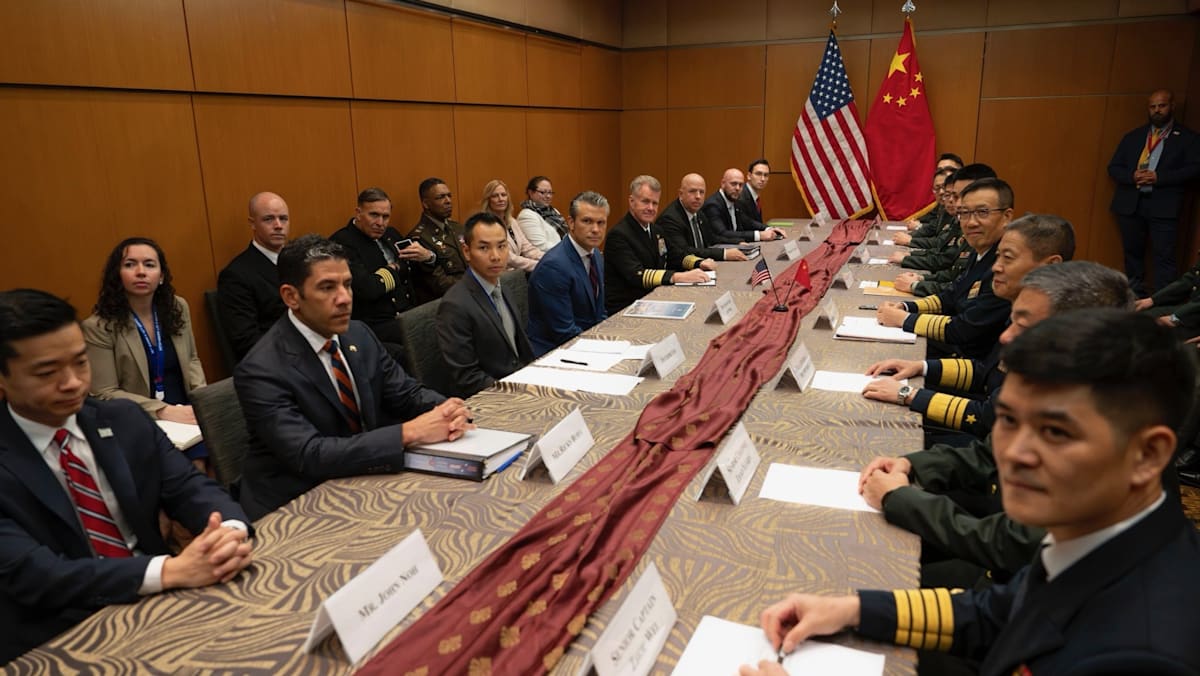

Yet, those concerns have faded. The US and China have de-escalated to 30 per cent and 10 per cent respectively, while Canada is holding off on retaliatory tariffs as they seek a trade deal with the US. Even the EU, whose trade ministers had created a “trade bazooka” to fire back at Washington, held back from confrontation.

There are several reasons for this acquiescence. In the case of the EU, the bloc was beset by internal divisions on how harsh retaliation should be. Many member states were unwilling to risk more economic damage to key industries such as distillers and pharmaceuticals. Some ostensibly wanted to absorb the tariff blow and move on, perhaps also holding out hope that Mr Trump would change his mind.

Nonetheless, a pool of evidence suggests that Mr Trump’s tariffs are bringing him foreign policy victories. Colombia agreed to receive militarised deportation flights after tariff threats, while both Canada and Mexico agreed to increase border security.

Call it appeasement, if you must. But most countries seemingly acknowledge that tariffs are the new cost of doing business with America, and that they will persist even beyond the Trump administration amid a lack of pro-trade voices in the American political landscape.

In response to a new normal with a more protectionist America, the most urgent need for governments would be to secure a relatively low tariff rate in comparison to neighbouring states.

A SHARP BUT BRITTLE WEAPON

Still, tariffs have their limits. They might be useful at forcing countries to the negotiating table – but emerging questions may blunt their effectiveness.

File photo. A container is loaded onto a cargo ship at Vietnam's Hai Phong port on Apr 16, 2025, after US President Donald Trump announced a 90-day pause on tariffs for many countries. (Photo: Reuters/Athit Perawongmetha)

File photo. A container is loaded onto a cargo ship at Vietnam's Hai Phong port on Apr 16, 2025, after US President Donald Trump announced a 90-day pause on tariffs for many countries. (Photo: Reuters/Athit Perawongmetha)

First is the issue of sanctity of agreements. If governments are to offer concessions, especially on security issues, in exchange for lower tariff rates, they must be assured that US officials will keep their word.

There are already indications of Mr Trump or his negotiators unilaterally changing the terms of deals.

Vietnam was reportedly dismayed by Mr Trump’s 20 per cent announcement, having believed its negotiators secured an 11 per cent tariff rate. Japanese trade negotiator Ryosei Akazawa pushed back against US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent’s claim that their trade framework would be reviewed quarterly.

No written text has been published for either deal, much less signed. Still, each report of an arbitrary change could make US partners more suspicious and less willing to cooperate with Washington’s demands.

Second is the issue of resolve. Given the number of times Mr Trump has backed down from hardline tariff positions or carved out exemptions, his targets may begin to treat his threats less seriously as they doubt his resolve.

Take, for example, the case of Brazil. Mr Trump just declared a 50 per cent tariff rate on Brazil for its “witch hunt” against his ally Jair Bolsonaro, its former president facing trial for an attempted coup.

Despite the hefty overall tariff, the blow was softened by the exclusion of several sectors, such as aircraft parts and orange juice. Brazilian Treasury Secretary Rogerio Ceron even remarked that it was a “more benign outcome than it could have been”.

As the 2026 midterm elections approach, more governments may doubt Mr Trump’s willingness to hurt his economic scorecard, creating diminishing returns for each new tariff threat.

MAKING LINKAGES A LIABILITY

More broadly, a third concern for Mr Trump is how his tariff policy is changing the policy calculations of US allies and partners.

His willing weaponisation of America’s economic leverage suggest that he would just as willingly use American technological or security links to coerce other countries. As researchers from the Washington think tank the Centre for a New American Security observed, Mr Trump’s tariff policy has led to concerns about dependence on US cloud service providers for artificial intelligence capabilities.

In the short term, governments are likely to play along with Mr Trump’s tariff threats to avoid a debilitating blow to their economies. They will offer concessions and likely grit their teeth if the terms of their deals are unexpectedly altered.

But under these circumstances, each successive tariff will conjure disgruntlement and suspicion, doubly so if Mr Trump later backs down. Moreover, they will reinforce the discomforting notion that any kind of reliance on America could become a liability.

Tariffs are undoubtedly a powerful weapon for the Trump administration, but they might undermine the network of partners and allies that made America a formidable power.

Kevin Chen is an Associate Research Fellow with the US Programme at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore. He writes a monthly column for CNA, published every first Friday.