SINGAPORE: After several weeks of suspended flights, seafood import bans, cancelled concerts performed to empty arenas, increased military activity, and even fire control radar lock-ons by fighter aircraft, Japan-China ties remain tense.

This most recent spat arose from Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s answer to parliamentary questions from opposition lawmaker and former foreign minister Katsuya Okada on Nov 7 about crisis scenarios involving a Taiwan blockade.

Ms Takaichi said that if China launched military action against Taiwan and attacked US military forces, this could pose a “survival threatening situation” for Japan but that any decisions must be considered comprehensively. The term “survival threatening situation” is an important one legally, as it denotes an existential threat to Japan and allows the activation of its self-defence forces.

She was the first sitting prime minister to describe such a concrete scenario.

Beijing blamed Japan and Takaichi for provocation and supporting Taiwan independence, demanding a retraction. The Chinese consul-general in Osaka even posted – then deleted – a Japanese-language social media comment that the “filthy head … must be cut off without hesitation”.

The heated language obscures the fact that there is a conflation of three distinct underlying points that explain why China-Japan tensions are unlikely to ease soon. Even after the current round of tensions blow over eventually, these areas of departure are likely to reappear as sticking points in relations between Tokyo and Beijing.

TAIWAN’S POLITICAL STATUS

First is the current political relationship between Japan and Taiwan.

Japan, like most countries, does not officially recognise Taiwan’s government, having broken off ties with the Republic of China in 1972. It established formal relations with the People’s Republic of China, with the communique stating: “The Government of Japan recognises that Government of the People's Republic of China as the sole legal Government of China.”

Equally important to note are the next two lines: “The Government of the People's Republic of China reiterates that Taiwan is an inalienable part of the territory of the People's Republic of China. The Government of Japan fully understands and respects this stand of the Government of the People's Republic of China, and it firmly maintains its stand under Article 8 of the Potsdam Proclamation.”

Japan’s position is that it understood and respected, not that it agreed with or accepted, Beijing’s position. The reference to the declaration that defined terms for Japan’s surrender further specifies that its post-World War II territories were limited to Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, Shikoku and other minor islands.

This is in keeping with the 1951 San Francisco Treaty, in which Japan renounced its claims to several territories, including Korea, Formosa (Taiwan), the Spratly Islands, the Paracels Islands and any part of the Antarctic area. Except for recognising the independence of Korea, it was not explicit to whom Japan relinquished control of these territories.

In other words, Japan and China agreed to disagree over Taiwan when establishing formal diplomatic relations, or at least chose to overlook their differences.

In this recent spat, Ms Takaichi and her government reiterated that they have not deviated from Japan’s “one China” policy. This means Japan officially recognises only the People’s Republic of China but leaves Taiwan’s status ambiguous.

This differs from Beijing’s “one China principle” which maintains that Taiwan is an inalienable part of China, of which the PRC is the sole legitimate government. Beijing has long been dissatisfied with the ambiguity in the San Francisco Treaty and its foreign ministry spokesperson recently called the document “illegal” and “invalid.”

A PHYSICAL REALITY

Second is the significance of Taiwan’s geographic location, separate from its political status.

Publicly available maps clearly indicate that the island sits astride sea lanes, air routes and submarine cables linking Southeast and Northeast Asia.

These connect Japan with international trade – most of its energy imports, telecommunications and financial markets going through Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean, Middle East, Africa and Europe.

People look across the strait from a lighthouse at the 68-nautical-mile scenic spot, one of mainland China's closest points to the island of Taiwan, on Pingtan Island, Fujian province, China, April 9, 2023. REUTERS/Thomas Peter

People look across the strait from a lighthouse at the 68-nautical-mile scenic spot, one of mainland China's closest points to the island of Taiwan, on Pingtan Island, Fujian province, China, April 9, 2023. REUTERS/Thomas Peter

Disruption from crisis or conflict would prove devastatingly costly for the world’s fourth largest economy – and for that matter, economies across East Asia for the same reasons.

The exchange between Mr Okada and Ms Takaichi could be read as a discussion over implications of Taiwan’s physical location rather than any change in Japan-Taiwan relations.

JAPAN’S DEFENCE DILEMMA

Third, there is also the matter of Japan’s alliance relationship with the United States, which makes it challenging for Ms Takaichi to walk back her comments.

US support for unfettered maritime access permits Japan to connect with far-flung markets and suppliers. Partnering with the US for security has historically enabled postwar Japan to not worry about military issues and invest in relations with its neighbours instead.

In a world where there are more questions about US commitment to a forward security presence in Asia, Japan may find that it must invest more in its own defence and be more openly supportive of its alliance relationship with the United States.

At any rate, Japanese public opinion currently backs Ms Takaichi and her administration. These considerations, in addition to Ms Takaichi’s need to call for elections soon, mean that she is unlikely to walk back her comments.

TENSIONS UNLIKELY TO RESOLVE SOON

Ms Takaichi’s comments are a reflection of Japan’s changing security calculus.

Even as it appreciates Japan’s more passive stance on security, Beijing sees the US-Japan alliance as a tool to “encircle, contain, and suppress” it. This is a position Chinese President Xi Jinping personally spoke about publicly in 2016 and subsequently reiterated.

Perhaps a motivation for Beijing’s aggravation towards Japan is to further isolate Taiwan and Japan. It could also put the Takaichi administration on the defensive early on, considering the new prime minister hails from the conservative and more hawkish side of Japanese politics toward which Beijing is traditionally wary.

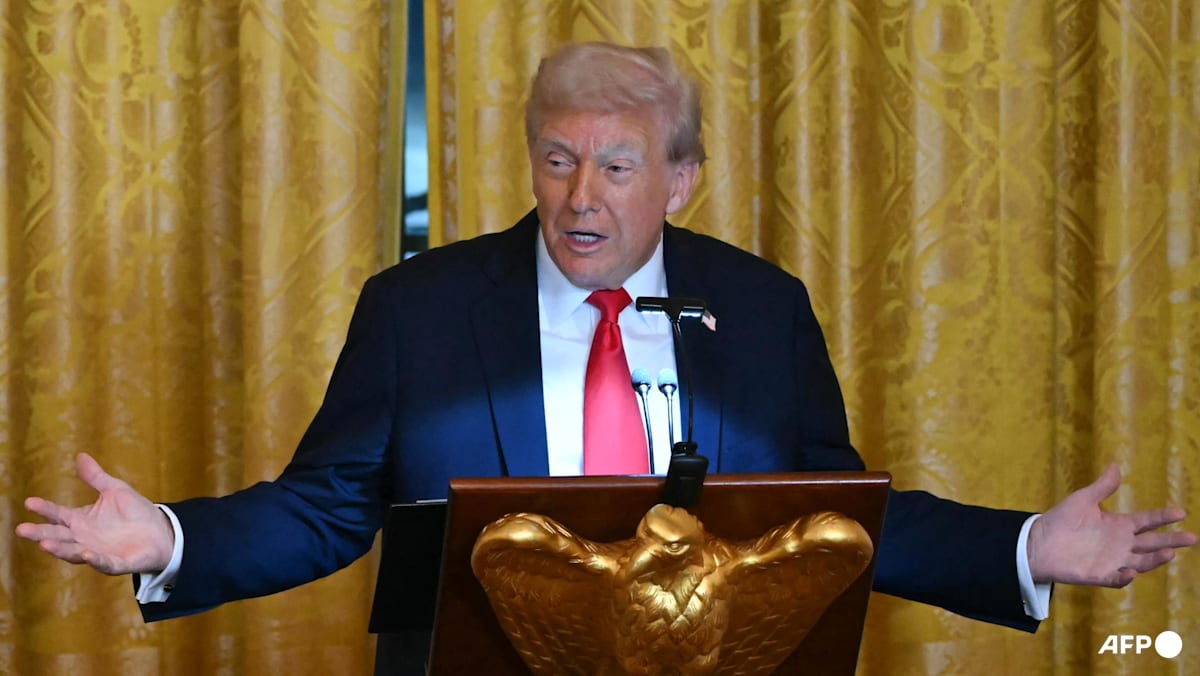

The Trump administration also has not vocally backed its ally amid Chinese pressure, even if it has sought to demonstrate the strength of the US-Japan alliance through shows of force. This may encourage Beijing to be even more assertive.

For now, the Takaichi administration is striving to remain calm and reduce drama. Japan appears to be managing Chinese economic coercion, despite bluster from Beijing.

Nonetheless, chances are that Japanese public apprehensions toward China will deepen even after tempers from the current episode eventually subside, making future disputes both more likely and potentially more severe.

UNFAMILIAR AND LESS COMFORTABLE CHANGES TO COME

Other countries in Asia have their own “one China” policies – determined as they see fit – to manage ties with Beijing and Taipei. These can and often do differ from the positions articulated by China, Japan or each other.

Like Japan, however, they cannot escape the fallout from a possible major crisis surrounding Taiwan simply because of geography.

Questions over how major powers may relitigate and reinterpret international laws and understandings remain.

For smaller nations, such changes erode key aspects of international practice that reduce transaction costs, enhance coordination, afford a degree of juridical equality, and provide some restraint on major power license.

How the current Japan-China spat plays out may well affect the longer-term interests of third parties in unfamiliar and less comfortable ways. These countries may wish to reference current Tokyo-Beijing tensions and consider how best to protect their equities and manage their vulnerabilities in a more uncertain, contentious and coercive world.

Chong Ja Ian is Associate Professor of Political Science at the National University of Singapore and a non-resident scholar at Carnegie China.