A rebound in populations of the fish shows capitalist self-interest and regulation can work together, says David Fickling for Bloomberg Opinion.

A knife cuts into a fatty cut of tuna at a market in Tokyo, Apr 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Ayaka McGill)

A knife cuts into a fatty cut of tuna at a market in Tokyo, Apr 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Ayaka McGill)

SYDNEY: In a world that often seems to be teetering on the edge of chaos, what hope is there for defenceless fish?

The Atlantic cod off the eastern coast of Canada were once such an abundant resource that their dried flesh helped drive the colonisation of the Americas, spawning local delicacies from Spanish bacalao to Jamaican ackee and saltfish. Industrialised harvesting caused a collapse in populations in the 1980s and 1990s, leading many diners to switch to monkfish instead – until that species, too, went into decline.

It can feel like an inevitable cycle. Humans seem incapable of carrying out the most basic measures to protect common resources from over-exploitation — whether it’s the carbon that we spew into the atmosphere, the plastics that we scatter through the environment, or wild animals that we’ve been hunting to extinction since the paleolithic era.

And yet on the high seas, there are encouraging signs that concerted efforts can reverse the process.

OUR INSATIABLE HUNGER

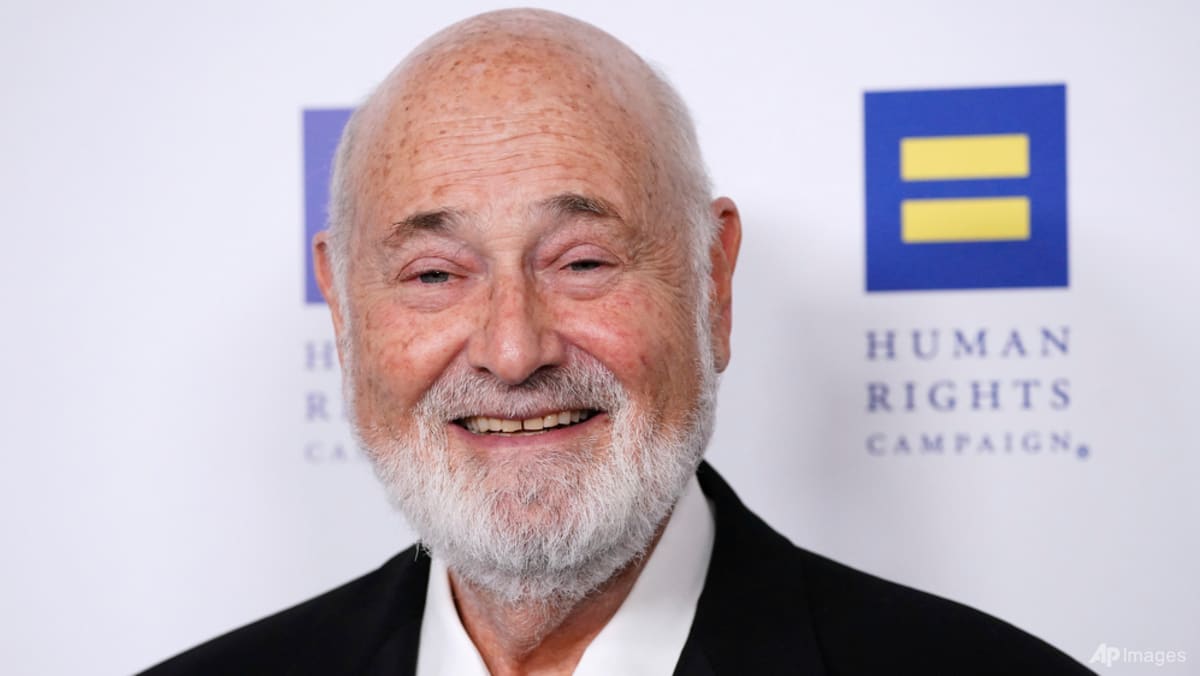

Take tuna. Like cod and monkfish, the most prized species once seemed to be on the verge of disappearance, thanks largely to our insatiable hunger for sushi.

The skipjack tuna that you’ll typically find in cans is super-abundant, but the three main species of bluefin tuna were in a much more precarious state. Bluefins are rarer, slow-growing and can be as long as a small car. Diners, particularly in Japan, prize their flesh for its complex, buttery taste, and fish sometimes sell for millions of dollars apiece.

The global catch fell by half between 2005 and 2011 as years of overfishing left populations too small to rebuild themselves. In 2010, a proposal to ban commerce in Atlantic bluefin came close to passing at the United Nations Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, a move that would have given it similar levels of protection to the rhinoceros and elephant.

The following year, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) warned that more than half of tuna species were facing extinction. There was “little hope of recovery” for the southern bluefin, one of the IUCN’s authors was quoted as saying.

ONE OF THE MOST SUSTAINABLE WILD FISH

That’s not what happened. The same year, the countries fishing the southern bluefin’s habitat in the Indian and Southern Oceans for the first time agreed on joint limits on how much they could catch.

Monitoring of fish stocks could provide a decent estimate of how many animals were out there, and how fast they were reproducing. By keeping the catch within reasonable bounds, the fishery could gradually rebuild to the point where populations were sustainable and exploitation was profitable.

The policy, along with similar measures to preserve other tuna species, was a remarkable success.

A revision to the IUCN’s endangered list in 2021 took the Atlantic bluefin from “endangered” to “least concern”; albacore and yellowfin, both seen as “near threatened” in 2011, were also moved to “least concern”. Southern bluefin, which had been seen as “critically endangered” since the 1990s, was lifted to merely “endangered”. As populations recovered, catches of the southern species nearly doubled, from 9,400 tonnes in 2011 to 17,000 in 2021.

Right now, tuna is probably one of the most sustainable wild fish you can eat. Some 99.3 per cent now comes from sustainable stocks, according to a report released by the Food and Agriculture Organization last week, with 87 per cent of stocks now being fished sustainably. That’s far better than the average 64.5 per cent of stocks across all fish species.

With the exception of Mediterranean albacore (a favourite of Spanish canneries) and bigeye in the Indian Ocean, every population is now being fished within sustainable levels. Compare that to Atlantic cod, where just 21.7 per cent of stocks are being fished sustainably, and the difference is stark.

Tuna is placed for sale at the food distribution centre of the warehouse and general stores company CEAGESP, in Sao Paulo, Brazil, Aug 5, 2025. (Reuters/Jorge Silva)

Tuna is placed for sale at the food distribution centre of the warehouse and general stores company CEAGESP, in Sao Paulo, Brazil, Aug 5, 2025. (Reuters/Jorge Silva)

REINING IN OVER-EXPLOITATIVE TENDENCIES

There’s a lesson in this: Capitalist self-interest, combined with intensive regulation, can work – even when it’s being driven by our obsession with particular high-value foods.

On land, we think of monocultures – the dominance of major food groups such as corn, apples and chickens – as a bad thing. In the ocean, where it’s inherently difficult to get a handle on just how many fish are lurking in the depths, monocultures can be beneficial. The fish that are most caught are, by and large, the ones that are best understood, and the easiest to manage sustainably.

Intensive management and catch quotas, like the rules helping the southern bluefin to recover, are also spreading beyond the richest countries to the likes of Thailand and Indonesia.

There’s no cause for complacency, however. Even fish being sustainably harvested could be just a few years away from an unexpected population collapse, and a growing human population with rising incomes and improving capture technology is inevitably going to maintain pressure on wild stocks for centuries to come.

Still, there’s nothing foreordained about our despoliation of the environment. In the seas, as on land and in the atmosphere, our efforts to rein in our over-exploitative tendencies can still find success.