ACEH, Indonesia: Two decades ago, the Indonesian province of Aceh emerged from nearly 30 years of brutal conflict between separatist fighters and the central government.

More than 15,000 lives were lost to guerrilla warfare that raged through mountains and villages, leaving deep scars on the region.

The turning point came in 2005 after a devastating tsunami prompted both sides to pursue peace.

The resulting Helsinki Agreement – signed on Aug 15, 2005 – brought an end to the bloodshed, granting Aceh special autonomy under the Indonesian government and the hope of a better future.

Peace has reigned in Aceh since then, but many say the promise remains only partially fulfilled.

ONLY 30% OF AGREEMENT CARRIED OUT: GOVERNOR

Pidie regency was once the epicentre of chaos and violence in Indonesia.

The regency used to be a stronghold of the Free Aceh Movement, or GAM – a separatist group that fought fiercely for independence from Jakarta.

Reminders of the past linger in Pidie, in particular, a staircase remains at the site of the former Rumoh Geudong which the Indonesian military used to torture civilians suspected of links to separatist rebels. Locals destroyed the building in 1998, fearing it might again become a place of abuse.

The Indonesian government has chosen a non-judicial path - one that focuses on restoring victims’ rights rather than holding perpetrators criminally accountable.

The approach has elicited mixed reactions and raised questions on what true reconciliation really means.

The Aceh Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established in 2013 to uncover what really happened during the conflict and help the province move forward.

However, the Aceh government says not all commitments under the Helsinki Agreement have been met.

Aceh received greater autonomy following the peace deal. It is also the only region in the country permitted to form local political parties, including the Aceh Party, led by Aceh’s governor Muzakir Manaf.

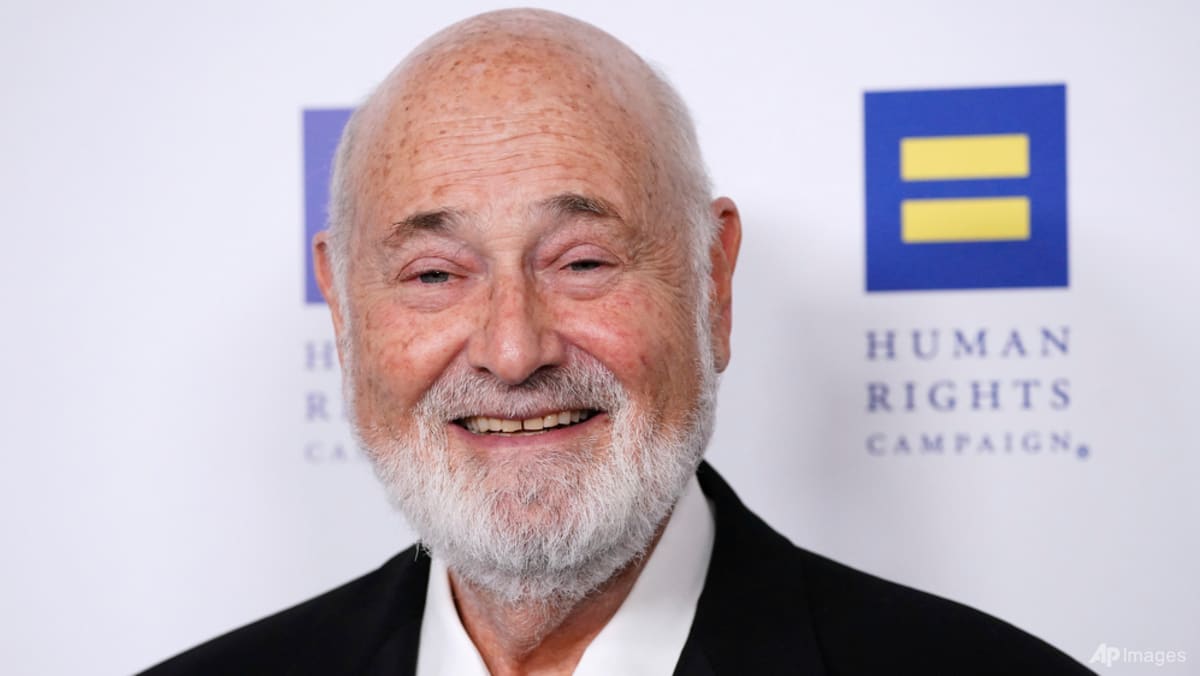

Manaf, who used to lead GAM’s armed wing, told CNA that only 30 per cent of the Helsinki Agreement has been carried out.

"This is the negligence of the central government. It means they’re not … really serious about taking action,” he added.

Manaf warned that if Jakarta is not serious, the dark chapters of Aceh's past could return.

“This has become a burden on us, and we hope that the central government, under President Prabowo Subianto’s administration, will finally see this through to completion.”

Muzakir Manaf, chairman of the Aceh Party and newly-elected governor, takes part in an inaugural ceremony in Banda Aceh on Feb 12, 2025. (Photo: AFP/Chaideer Mahyuddin)

Muzakir Manaf, chairman of the Aceh Party and newly-elected governor, takes part in an inaugural ceremony in Banda Aceh on Feb 12, 2025. (Photo: AFP/Chaideer Mahyuddin)

A point of contention is the right to use regional symbols, including a flag, a crest and a hymn.

The moon-and-star flag remains a deeply emotional and political issue in Aceh. While the Aceh regional parliament approved the flag as a local symbol in 2013, the central government in Jakarta has not recognised it, citing concerns about its separatist symbolism and potential to provoke unrest.

This means raising the flag remains a sensitive and potentially provocative act, especially during key dates like the peace anniversary.

COMMITTED TO FULFILLING DEAL: JAKARTA

The Indonesian government has said it remains committed to fulfilling the terms of the peace deal.

For instance, Prabowo stepped in to mediate a recent territorial dispute, affirming that four islands that were contested between Aceh and North Sumatra fall under Aceh’s jurisdiction.

Indonesia’s Law Minister Supratman Andi Agtas told CNA that Manaf, as governor, now has “an intense and very good relationship and communication” with Prabowo.

Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto delivers his annual State of the Nation Address ahead of the country's Independence Day, in Jakarta, Indonesia, Aug 15, 2025. (AP/Bay Ismoyo/Pool)

Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto delivers his annual State of the Nation Address ahead of the country's Independence Day, in Jakarta, Indonesia, Aug 15, 2025. (AP/Bay Ismoyo/Pool)

“So, when we talk about commitment, like it or not, it has to be followed through, because Aceh is, after all, an integral part of Indonesia,” Supratman added.

“What’s most needed now is how we can help the people of Aceh move forward.”

HOW DEMOCRACY IN ACEH HAS EVOLVED

Analysts said democracy in the province is maturing as national political parties make inroads, with a more balanced democratic system emerging in the 2019 and 2024 legislative elections.

“Even national parties that barely had any support in Aceh before, like the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle, managed to win a seat. That has rarely happened before, getting a seat in parliament,” noted Teuku Zulkarnaen, dean of the faculty of social and political sciences at Malikussaleh University.

In Aceh’s parliament, nine national parties currently hold 55 of the 81 seats. The Aceh Party is the largest party and was formed by former GAM members.

Manaf said his party hopes for Aceh’s interests to be prioritised and people’s welfare to improve, especially with the high rate of unemployment.

Data from the Central Bureau of Statistics (Aceh province) showed that the unemployment rate in Aceh was 5.5 per cent as of May this year. This is higher than the national unemployment rate of 4.76 per cent.

“Our mission and vision in the next five years is to continue moving Aceh forward. We can at least reduce unemployment,” Manaf added.

The 61-year-old won the Aceh gubernatorial election last year and was sworn in as governor in February.

Supratman said Aceh’s democratic process has been progressing well, adding that he hopes it can serve as an example for the future development of democracy across Indonesia.

Indonesia’s law ministry oversees the registration of local political parties in Aceh and approves their participation in elections.

“Any future laws must include Aceh’s special provisions and refer to the Law on Aceh Governance. Local representatives must be involved in policymaking – that is a legal mandate,” he noted.

Looking ahead, much of Aceh’s future lies in the hands of its younger generation, many of whom are too young to recall the violence that once gripped their province.

Young Acehnese told CNA that while they still respect the peace legacy, they are increasingly focused on performance, inclusivity and accountability.

“For me, I have an open mind. As long as someone is truly capable of managing Aceh, then by all means, why not?” said Generation Z resident Muhammad Joni Asnawi.

“It doesn’t necessarily have to be someone who is a former GAM member or anyone in particular. It should be whoever is truly qualified to lead Aceh."

AMONG INDONESIA’S POOREST PROVINCES

But in just two years’ time, the province’s multi-billion-dollar special autonomy fund from Indonesia’s central government is set to expire.

The provincial government hopes this fund – aimed at boosting infrastructure development and reducing poverty – will be extended indefinitely beyond the 2027 deadline.

Despite these extra monies and its vast natural resources, Aceh continues to rank among Indonesia’s poorest provinces.

Lhokseumawe, Aceh’s second-largest city, was once known as the petrodollar city due to its major role in Indonesia's gas production in the 1980s and 1990s.

Its natural gas fields were heavily guarded during the conflict, with rebels often targeting them to disrupt operations as they were seen as symbols of the state’s economic power in the region.

With much of its revenue being directed to the central government, Aceh felt it was not benefiting fairly from its own wealth. This perceived economic injustice was a key factor in GAM’s rise.

CORRUPTION A PERSISTENT ISSUE

Civil society groups say the real problem now is not funding, but instead how the money has been managed.

Corruption in Aceh, like in many other regions in the country, is a persistent problem.

"All this time, we’ve lost direction. Take the special autonomy fund for example - US$6.7 billion has already been disbursed. What else does Aceh want?” questioned Alfian, a coordinator at anti-corruption non-governmental organisation Aceh Transparency Society.

“If we’re talking about a roadmap, the truth is, we don’t have one. That’s why the current effort is focused on ensuring that (the special autonomy) fund continues permanently with support from the central government. I believe we need a new formula.”

Acehnese men cycle to work past an Exxon Mobil gas production facility in Lhokseumawe, Aceh province, Indonesia, Apr 4, 2001. (File Photo: AP/Ed Wray)

Acehnese men cycle to work past an Exxon Mobil gas production facility in Lhokseumawe, Aceh province, Indonesia, Apr 4, 2001. (File Photo: AP/Ed Wray)

In the meantime, Acehnese like Abdul Manaf, 63, will continue struggling to make ends meet.

The Lhokseumawe resident, who makes palm sugar from sap and sells his product in the markets, said life in the city is “heartbreaking”, especially due to a lack of water.

“We have to carry water from more than a kilometre away just to drink and bathe. That’s what we’re going through right now. It’s truly disheartening,” he lamented.

Even if the vision of prosperity is a distant one, Aceh governor Manaf remains optimistic it will continue getting special autonomy funds from the central government.

“This is what we need - to rise up and break free from that poverty,” he added.