For Mrs Iris Than, the best way to get to know Singapore’s politicians is not by talking to them at Meet-The-People Sessions or during walkabouts, but rather by watching their videos and reading the comment sections on Instagram and TikTok.

The 33-year-old sustainability manager said: “In-person interactions tend to be very brief, seldom and superficial, perhaps due to their busy schedules, so I appreciate the Instagram posts and comments as an ongoing channel of interaction.”

She is typical of a growing number of voters here who mainly interact with Members of Parliament (MPs) and opposition party members online.

Mrs Than has become used to seeing the likes of Prime Minister Lawrence Wong engaging in informal interviews on podcasts or with social media personalities in unconventional settings. Once, Mr Wong took part in a video where he discussed the national Budget at a cat cafe.

Of course, politicians in Singapore have used online media to engage with their constituents for almost as long as these platforms have existed. However, especially since the last General Election in 2020, they have become more important than ever.

That election held in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic was a watershed event that proved just how crucial online platforms are for engaging voters, when rallies at physical sites were not possible.

Opposition figures such as Dr Tan Cheng Bock, now chairman of the Progress Singapore Party (PSP), captured the attention of younger Singaporeans by embracing lingo such as “hypebeast” and “woke” in interviews and online posts that quickly went viral.

Dr Tan, who was contesting in West Coast Group Representation Constituency (GRC), amassed thousands of followers on Instagram throughout the hustings. Today, he remains one of Singapore’s most-followed opposition members on the platform, with 56,000 followers.

The 84-year-old has said that he has not ruled out standing for the next election.

Progress Singapore Party's Tan Cheng Bock (right) showing the hand gesture for "love" or "heart" popularised by South Korean artistes, when meeting young constituents during the General Election campaign in 2020. (Photo: CNA/Ooi Boon Keong)

Progress Singapore Party's Tan Cheng Bock (right) showing the hand gesture for "love" or "heart" popularised by South Korean artistes, when meeting young constituents during the General Election campaign in 2020. (Photo: CNA/Ooi Boon Keong)

Dr Carol Soon, who led a study by the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS) on media and internet use during the last two elections, noted that the relative political importance of various online platforms have shifted over time.

The popular blogs and alternative online sites of 2011 were supplanted by Facebook in 2015, when that social media behemoth became the public’s top choice for election-related information.

Then in 2020, short-form video platform TikTok, along with podcasts, paved new ways for candidates to reach voters, heralding a trend that will only grow in the coming election, she said.

Dr Soon, associate professor of communications and new media at the National University of Singapore (NUS), added that as platforms that were primarily used by younger audiences have also become popular with older generations, candidates now have no choice but to include online media as a primary outreach tool.

Increasingly prominent in the online media toolkit are podcasts and short-form videos, formats that help politicians appear more relatable, away from their official duties that include giving formal speeches.

These trends mirror political strategies seen overseas. In the United States, for instance, re-elected President Donald Trump favoured appearances on podcasts and social media influencers' platforms over mainstream media outlets during his 2024 campaign trail.

Still, a strong online presence does not always translate into electoral success.

Some experts pointed to the example of presidential hopeful Ng Kok Song, whose social media-heavy campaign at the Presidential Election in 2023 did not result in significant support at the polls. That election was won by Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam in a landslide.

As the General Election predicted to be held as early as next month approaches, candidates and voters alike are preparing for an election cycle that will likely be shaped more than ever by digital engagement.

However, with finite resources, how are parties balancing social media outreach with face-to-face interactions?

With the release of the Electoral Boundaries Review Committee report on Tuesday (Mar 11) marking a key step toward this year's election, CNA TODAY takes a closer look at how political parties, potential candidates and social media influencers are shaping their positions for the digital game plan.

HOW NEW MEDIA HAS HAD AN IMPACT ON RECENT GLOBAL ELECTIONS

What is happening in Singapore in the lead-up to its next election mirrors international trends during 2024, a year when a large number of elections were held across the globe.

Politicians around the world handled emerging forms of media in their campaigning apparatus. In the United States, then-presidential candidates Donald Trump and Kamala Harris used podcasts to connect with voters.

Sidestepping traditional outlets, Mr Trump sat for a three-hour-long interview with Mr Joe Rogan, one of the most popular podcasters in the world. Mr Rogan's interviews with Mr Trump, vice-presidential candidate JD Vance and American billionaire Elon Musk before the election have since racked up a combined total of some 96 million views on YouTube.

Another feature of electioneering that has appeared more recently is artificial intelligence (AI).

AI proved to be a double-edged sword during the elections in India. There were plus points, including an AI tool that helped Prime Minister Narendra Modi to campaign more efficiently when his Hindi speech could be translated to Tamil in real-time.

However, AI also distorted reality. Several public figures in India who had died years ago suddenly "resurfaced" on the internet and appeared to be giving speeches encouraging people to vote in the election – these were deepfakes generated by AI.

Some of these videos went viral and spread misinformation across the country. Other AI-generated material included automated calls to voters that impersonated candidates.

The Singapore authorities have already made moves to prevent AI from wreaking such havoc in the upcoming election here.

Singapore’s parliament passed a law in October last year banning deepfakes and other digitally manipulated content during the election.

It would be illegal to publish, share or repost such content if it has certain characteristics. These include depictions of candidates saying things that they did not say, as well as fake content that appears realistic enough that people might believe it.

There is still some room for AI adoption though. The Ministry of Digital Development and Information said that minor modifications such as beauty filters are allowed, as well as animated characters that are not realistic.

Dr Carol Soon, associate professor of communications and new media at the National University of Singapore (NUS), said that when it comes to discussions about AI and elections, people typically think about AI being used for producing public-facing communications and their attendant pitfalls, which she believes “is a very limited view of AI”.

AI tools can help to increase operational efficiency before and during campaigning, when parties may use them for scheduling and budgeting tasks.

“AI can also be used to help develop campaign materials, like coming up with first drafts for campaign speeches and other party communications,” Dr Soon added.

This could level the playing field between more well-resourced and less-resourced parties, she said, pointing to how smaller parties who have tighter budgets may benefit from AI since many tools are free or only come with a small fee.

Associate Professor Natalie Pang said that dashboards now have AI-powered analytics, which she expects political parties to use behind the scenes to monitor online chatter. A dashboard may consist of a collection of interactive charts and graphs generated by AI.

The head of the communications and new media department at NUS added: “Based on what’s happening online, they could be adjusting their speeches, their narratives and so on as the election gets started.”

Collapse Expand

HOW PARTIES ARE USING ONLINE MEDIA

The official social media pages of political parties may highlight the work that they are doing on the ground or snippets of parliamentary debates, but individual politicians or party members often have their own respective social media accounts, where they strive to project an authentic persona and engage with their constituents directly.

In the case of the ruling People's Action Party (PAP), MPs are mostly left to their own devices in managing their own social media accounts. Some political office-holders use their personal accounts to engage their constituents and amplify the work of their ministries at the same time.

PAP told CNA TODAY that the party does not take a “one-size-fits-all approach” to social media.

“Our MPs speak up on various issues that they and their residents care deeply about. Our MPs have different personalities and leverage social media in their own ways.”

As a first-time candidate in the 2020 General Election, MP Mariam Jafaar (PAP-Sembawang GRC) said that social media was key to connecting with constituents when she entered the public eye.

“As I was new, and (the election) was during the pandemic, I tried to be disciplined about posting once a day, to help people know me, my activities and programmes, my points of view.”

She now posts event pictures, profiles of Woodland residents and snippets about her personal life, which tend to be the most popular posts.

“I am not ramping up my (social media) presence during the run-up to elections. Practically speaking, the time I have for social media is limited. My priority is always getting things done on the ground,” she added.

Member of Parliament Mariam Jafaar posts photos of events and snippets of her personal life on her social media accounts. (Photos: Instagram/Mariam Jafaar)

Member of Parliament Mariam Jafaar posts photos of events and snippets of her personal life on her social media accounts. (Photos: Instagram/Mariam Jafaar)

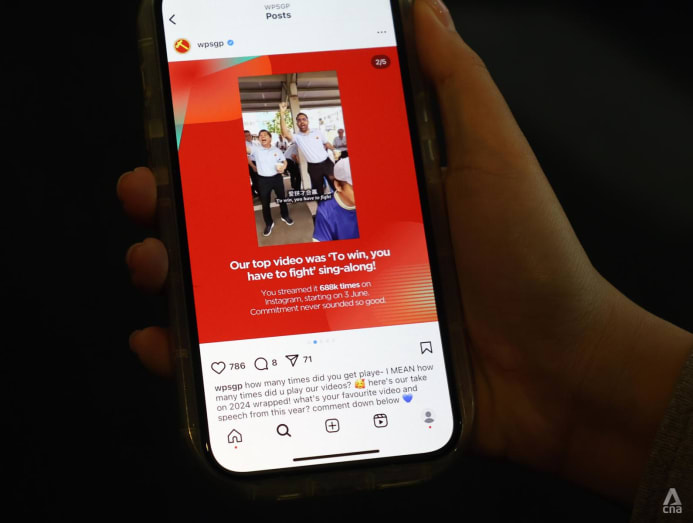

Opposition parties said that social media is vital to level the playing field and reach Singaporeans directly, though many of them operate with limited resources and rely on volunteers to handle their social media accounts.

A representative from the Workers’ Party (WP) said that it maintains an “active presence” on all major social media platforms, including TikTok, where it launched an account in 2022.

“Social media is a powerful equaliser in political engagement, and the party leverages digital platforms to connect with people wherever they are most comfortable.”

This includes structured infographics, explainer videos for policy initiatives, the promotion of grassroots events, volunteer and voter outreach, as well as candid content that have a “human touch”.

Social media has also helped in amplifying the opposition party’s key milestones, such as the launch of the WP documentary on Hougang constituency late last year during its 67th anniversary, the party added.

“While WP continues to experiment with and refine its digital outreach, it sees social media as a complement – not a replacement – for the party’s long-standing commitment to ground engagement.”

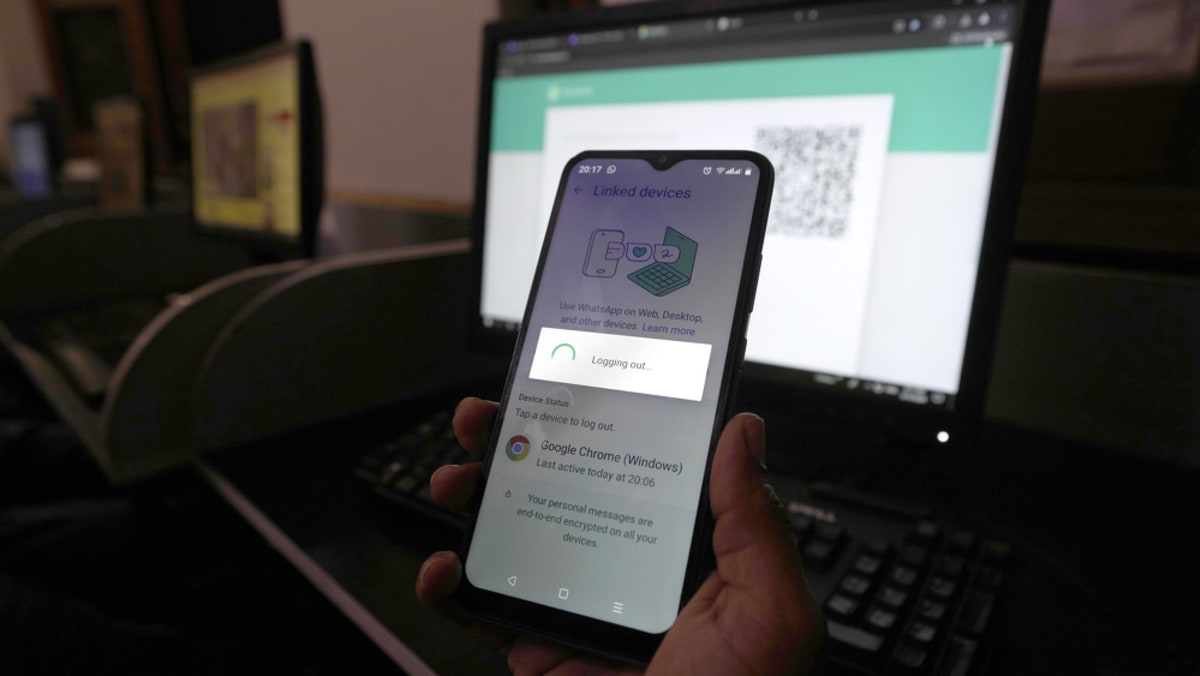

A video post on the Instagram account of the Workers’ Party, seen on a mobile phone on Mar 13, 2025. (Photo: CNA/Ooi Boon Keong)

A video post on the Instagram account of the Workers’ Party, seen on a mobile phone on Mar 13, 2025. (Photo: CNA/Ooi Boon Keong)

For the Singapore Democratic Party (SDP), its key members typically manage their own social media profiles with some help from volunteers.

“Social media has generally been a very effective tool for reach and engagement. We are obviously able to have more control over our messaging on owned channels and can also easily and directly connect with our audience or followers,” it said.

Dr Paul Tambyah, the party's chairman, said that he takes a serious, straightforward and factual tone online to highlight issues that are of concern to Singaporeans, such as cost-of-living pressures.

“There are many online trolls out there but paradoxically, every engagement – whether positive or negative – helps to get the message across because it bumps up our posts in the various algorithms,” he added.

SDP's vice-chairman Bryan Lim said that social media has been effective in overcoming “some of the weaknesses of ground work”, including connecting with constituents to whom he is unable to speak at length.

And even though social media is commonly seen as being used more by the young, Mr Lim said that surprisingly, a majority of those viewing SDP’s TikTok content are users in their 50s and 60s.

Mr Ravi Philemon, the secretary general of opposition party Red Dot United, which debuted in 2020's election, said that social media is crucial for a young party coming up against parties that already have large, established groups of followers.

“We are a party without parliamentary presence. If you have a parliamentary presence, you have a big advantage because the speeches you make are being recorded, the newspapers report on you. So I’m very mindful of that and (am figuring out) how then we can become relevant.”

His party’s social media team, which consists entirely of volunteers, “has their hands full” repurposing content from in-person ground engagements for their social media platforms, he added.

BYPASSING FILTERS TO APPEAR AUTHENTIC

As those in the political arena have harnessed the power of social media to endear themselves to Singaporeans, the means and formats of doing so have only expanded.

Research fellow Teo Kay Key from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy said that before social media, politicians used platforms such as posters, broadcasts or rallies, which are primarily “one-sided touch points”.

However, social media channels allow viewers to leave comments or interact real-time with the content creators, which also allows the people who push out content to quickly assess how audiences are reacting to campaign messages, for example.

Associate Professor Natalie Pang, head of the communications and new media department from NUS, said: “In the context of an election, there are a few things that politicians need to do. They need to communicate their political campaign, but they also need to be likeable. In a way, it’s a popularity contest.”

This has been bolstered by podcasts entering the mainstream, as audiences may tune in to interviews with political heavyweights in the span of a commute, when carrying out daily tasks or while working out at the gym.

Yah Lah But, The Daily Ketchup Podcast and Plan B have earned dedicated followings by releasing long-form podcast episodes focused on current affairs, occasionally featuring conversations with political office-holders and opposition party members.

Supplier account manager Emily Su, who is in her 30s, listens to Yah Lah But “almost religiously, at least twice a day”.

She said that podcasts make her feel like she is having a conversation with friends, and that this intimacy and touch of humour “is lacking in mainstream media where delivery and tone are more formal”.

Podcasts hosts and viewers alike said that one draw of the format is that guest speakers have the airtime to share personal anecdotes alongside complex policy discussions.

Musician Er Chow-Kiat, 36, said that he enjoyed Prime Minister Lawrence Wong’s appearance on The Daily Ketchup Podcast where Mr Wong explained how a self-employed musician can still make a good living.

In response to a podcast host's concerns about his child potentially not having the chance to pursue a music career in Singapore, despite Mr Wong's call to embrace a broader definition of success, the prime minister said that musicians could diversify into performing, teaching, being an audio engineer and producer to support a career.

Mr Chow said: “I like that he was very candid and open for discussion. He seems to know what is happening on the ground and is trying his best to tackle these issues.”

Prime Minister Lawrence Wong (right) being interviewed on The Daily Ketchup Podcast in January 2025. (Photo: The Daily Ketchup Podcast)

Prime Minister Lawrence Wong (right) being interviewed on The Daily Ketchup Podcast in January 2025. (Photo: The Daily Ketchup Podcast)

Research by Dr Kenneth Paul Tan from the Hong Kong Baptist University showed that podcasts tend to be unscripted and unconstrained “by slogans and soundbites”.

The professor of politics, films and cultural studies published a paper titled Podcasting Politics in Singapore: Hegemony, Resistance and Digital Media.

He explained in the paper how the medium allows politicians to use colloquial expressions to “tell compelling stories in an expressive, humorous and sometimes self-deprecating manner”.

Politicians can thus connect with listeners emotionally and use interactive methods to get their response, thereby making listeners feel special and “transporting them into these politicians’ narrative world to gain their empathy and support”, Dr Tan wrote.

PODCASTS AND POLITICS

Producers and hosts of four podcasts in Singapore told CNA TODAY that interest from politicians who want to appear on their platforms has swelled since 2020, particularly in the run-up to this year’s election, which must be held by November.

A representative from Plan B said that episodes that gain the most traction include ones where political figures "go beyond talking points" to share personal experiences and behind-the-scenes insights.

“Long-form conversations also reveal more about a politician’s personality, values and vision. It’s an opportunity for them to connect directly with the public, explain their policies in detail and even address misconceptions.”

Mr Daniel Lim, host of The Daily Ketchup Podcast, raised an example of one well-received interview with Dr Chee Soon Juan, the secretary-general of SDP, which allowed audiences to “get to know his personal struggles, motivations and evolution over the years”.

Mr Lim said: "In Singapore, where the government scouts for the brightest talent during their academic years and draws talent from the civil service, we have a lot of technocrats that are introverted and private. A long-form podcast allows us to better draw out their stories and personalities."

Opposition party leader Chee Soon Juan (second from right) being interviewed on The Daily Ketchup Podcast in December 2022. (Photo: The Daily Ketchup Podcast)

Opposition party leader Chee Soon Juan (second from right) being interviewed on The Daily Ketchup Podcast in December 2022. (Photo: The Daily Ketchup Podcast)

Mr Terence Chia and Mr Haresh Tilani who host podcasts on Yah Lah But have conducted seven interviews with political figures from both sides of the aisle, including National Development Minister Desmond Lee and Mr Leong Mun Wai, a Non-Constituency MP from PSP.

Mr Haresh said that one attraction for listeners is the ability to continue the conversation even after the podcast has ended.

The podcast has an active community on online forum Reddit, where listeners sometimes write "essay-length" responses dissecting episodes and offer constructive feedback, he noted.

"It's a learning process for us also on how to interview people with so much influence, so much status. Our audience members do point out, 'Maybe you could've asked this or that', and it's something for us to reflect on."

One highlight for Mr Chia was when presidential candidate Tan Kin Lian was interviewed in 2023, during which he asked Mr Tan about his take on the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) community.

Mr Tan's response at the time – “If you want to be a homosexual, do it privately” – sparked great discussion among viewers, Mr Chia recalled.

In August 2023, Mr Haresh Tilani and Mr Terence Chia (right) interviewed then presidential candidate Tan Kin Lian (centre) who was a guest on a Yah Lah But podcast episode. (Photo: Yah Lah But Podcast)

In August 2023, Mr Haresh Tilani and Mr Terence Chia (right) interviewed then presidential candidate Tan Kin Lian (centre) who was a guest on a Yah Lah But podcast episode. (Photo: Yah Lah But Podcast)

Not all podcasts are the same. Some heavily feature policy analysis, while others lean into more personal storytelling, humour or rigorous debate.

For example, Associate Professor Walid Jumblatt Abdullah, who teaches political science at Nanyang Technological University, said that his podcast Teh Tarik with Walid, which is livestreamed on Instagram, is more focused on serious political analysis than many others.

He would not “waste his questions” by asking politicians about personal matters or try to draw out their personality, he added.

“I am not a fan of humanising politicians. I don’t care whether they are good fathers. I think that’s irrelevant to me," he quipped.

“Of course, there’s time for levity, but you can ask difficult questions in a light-hearted way. I do think that light-heartedness gives you cover to ask the difficult questions."

There is also a difference between how PAP and the opposition parties use podcasts. Dr Tan from Hong Kong Baptist University said in his research paper that PAP’s focus seems to be on humanising its image and portraying senior politicians as approachable figures.

Whereas for the opposition, podcasts provide a "rare avenue to challenge the status quo, articulate alternative visions and connect directly with citizens in a manner that legacy media has historically constrained”.

He also said that the opposition has long faced structural barriers in getting its message across, so podcasts offer the parties an opportunity to introduce fresh voices to the electorate and shape public perceptions.

KEEPING UP WITH TRENDS

Going beyond amplifying their work, some politicians have leaned into "trendjacking" – jumping on viral trends that tend to be most popular among young audiences.

These days, short-form videos are all the rage as they dominate the social media landscape, as was evident during Singapore’s 2023 presidential election.

Then, there have been trends that came on strong and faded away over the years.

Professor Crystal Abidin, a professor of internet studies at Australia's Curtin University, observed that in 2020, for example, influencers were a key medium for election candidates.

One such influencer was Ms Preeti Nair, better known by her moniker Preetipls, who interviewed opposition candidates such as Dr Chee from SDP and Mr Jose Raymond from the Singapore People’s Party for her YouTube channel during the 2020 General Election.

Ms Nair, who said that these were not paid collaborations, told CNA TODAY: “Many opposition candidates don’t have the same kind of platform (as PAP), so I felt it was important for my audience to hear directly from (them).”

She stressed that interviewing candidates is not the same as endorsing them and that she is open to hosting any candidate for a conversation, regardless of party affiliation.

“My goal is to create conversations that help my audience understand different perspectives firsthand.”

In a YouTube video, Ms Preeti Nair (right), better known by her moniker Preetipls, interviewed opposition candidate Jose Raymond (left) from the Singapore People’s Party during 2020's General Election. (Photo: YouTube/Preetipls)

In a YouTube video, Ms Preeti Nair (right), better known by her moniker Preetipls, interviewed opposition candidate Jose Raymond (left) from the Singapore People’s Party during 2020's General Election. (Photo: YouTube/Preetipls)

However, Prof Crystal noted that the upcoming election may see a shift from influencer-driven engagement, as scepticism grows towards influencer-led messaging.

Agreeing, Dr Tan from Hong Kong Baptist University said that politicians relying on influencer collaborations could appear "artificial or opportunistic".

"If influencers appear to be co-opted rather than genuinely engaged, their credibility and, by extension, that of the politicians they promote, can take a big hit," he added.

Instead, political figures are becoming content creators themselves, embracing short-form videos or live streams and responding to online users directly via “Ask Me Anything” sessions on their own social media accounts.

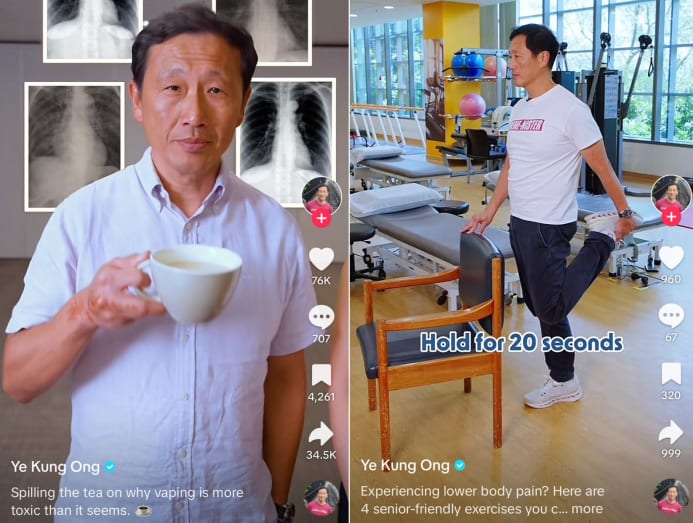

Health Minister Ong Ye Kung (PAP-Sembawang GRC), for example, offers a “masterclass” on how to capitalise on trends to highlight issues, Prof Crystal noted.

Mr Ong is one of the most-followed government ministers on social media, averaging more than 150,000 followers across Facebook, Instagram and TikTok.

His TikTok videos, which include low-impact exercise ideas and humorous skits about the harms of vaping, have garnered 1.3 million likes to date.

In response to CNA TODAY’s queries, he said that he uses social media actively because it can be an effective and compelling platform to communicate with a wider audience.

“Often, I will have an idea on what we should tell the public, my team will conceptualise the video and I may chip in. On the day of filming, we may change things drastically on the fly,” he revealed.

“The challenge is that social media is evolving all the time, and my team and I have to constantly explore new concepts. I used to do a series where I tried different sports. That format became less interesting after a while and we moved on to other concepts to promote physical fitness.”

Health Minister Ong Ye Kung (above) is one of the most-followed ministers on social media, averaging more than 150,000 followers across Facebook, Instagram and TikTok. (Photos: TikTok/Ong Ye Kung)

Health Minister Ong Ye Kung (above) is one of the most-followed ministers on social media, averaging more than 150,000 followers across Facebook, Instagram and TikTok. (Photos: TikTok/Ong Ye Kung)

Despite his social media success, Mr Ong said that he is still dedicated to in-person home visits, Meet-The-People Sessions and "sitting in coffee shops".

“I’m often surprised by young people and seniors who approach me warmly to talk about my videos and how they have resonated with them, before we launch into other discussions.”

For MP Louis Ng (PAP-Nee Soon GRC), creating content on his social media account is his means of encouraging Singaporeans to “pay a bit more attention” to what goes on in parliament.

“I will go into the sea, I will come out of a dustbin, to bring the very serious issue of climate change down to a lay person’s perspective,” Mr Ng said, referring to some of the things he has done to highlight these issues in Instagram videos.

Given each platform’s unique ethos and norms, the bar is raised for political figures trying to build a social media presence.

Many are increasingly finding success on TikTok, where content often goes viral on a post-by-post basis.

Mr Philemon from Red Dot United noted that posts on the party's TikTok account have received more than 13,000 likes overall, which puts it “in the league of the larger political parties”, even though the account has about 1,900 followers so far.

In the interim between elections, the opposition party posts videos, animations and a Thursday Talk segment on Facebook to keep policy discussions engaging.

“From the beginning, we were very clear that politics is a marathon. Nobody can live their life in five-year cycles, and a lot of things can happen in the five years between elections,” Mr Philemon said.

Politicians succeed if they are game to be “very flexible” with the format of the content posted, Prof Crystal said. This includes experimenting with audio choices, skits, memes and catchphrases that the algorithm will push to users.

“It’s a very difficult game to play because there’s no barometer. It could change from today to tomorrow and it changes from platform to platform. So you really need to have a team that’s on the ground and sensitive to how social media works,” she added.

Mr Ravi Philemon (above), secretary-general of opposition party Red Dot United, said that posts on the party's TikTok has received more than 13,000 likes in total so far. (Photos: TikTok/Red Dot United)

Mr Ravi Philemon (above), secretary-general of opposition party Red Dot United, said that posts on the party's TikTok has received more than 13,000 likes in total so far. (Photos: TikTok/Red Dot United)

CAN TIKTOK VIDEOS SWAY VOTES?

Social media can amplify a politician’s reach and make them appear more relatable, but it can also invite greater scrutiny.

Experts pointed to the case of former PAP candidate Ivan Lim, who withdrew from the 2020 election race after his conduct during his time in National Service and other accusations went viral online.

Assoc Prof Walid pointed out that appearances on online platforms that promise a more candid atmosphere can backfire for candidates who fail to demonstrate substance in such a long-form format.

Going viral or being a success online also does not always translate into electoral gains.

Dr Soon from NUS said that although viral content can increase awareness of candidates and political parties, credibility and a proven track record remain key when it comes to voters' decision-making.

“At the end of the day, it is who people think would deliver that matters, whether it is to provide more jobs, reduce the cost of living or strengthen alternative voices in parliament,” she added.

And even though social media allows candidates to broadcast their messages nationally, elections are ultimately decided at the constituency level.

“It would be a faux pas if candidates let up on walking the ground, meeting people or speaking with residents in-person,” Dr Soon said.

Indeed, voters have mixed views about how online content will inform their decision come Polling Day.

Podcast listener Kenneth Lee, a 39-year-old strategic communications consultant, said that he could be swayed to vote for a certain party if he is moved by a candidate's take on “serious bread-and-butter issues” on one of the podcasts he listens to daily.

Similarly, it has been years since operations manager Dominique Lee has interacted with an MP in person, but the 29-year-old spends three to four hours a week watching political podcasts.

“In my experience, listening to politicians in videos and podcasts definitely humanises them more, as they speak in more laidback settings. So interacting with politicians through this medium would definitely sway my vote in either direction,” Mr Lee said.

For first-time voter Ahmad Amsyar Adom, a 24-year-old undergraduate, he takes social media content by political party members with a “pinch of salt”, wary that such content can be carefully crafted to enhance the person's public image.

Some politicians succeed in presenting themselves as fun and relatable, but others come across as “really cringe” because it exposes how “out of touch” they are, he said.

Prof Crystal from Curtin University emphasised that social media’s reach is limited by the demographic on the platform.

TikTok videos, for instance, could go viral beyond the hyperlocal context, or be mainly reaching younger Singaporeans who may not yet be eligible to vote.

“Something that goes viral on TikTok with a million views will not translate to a million votes, but I can still see the value of warming up your prospective generations of voters to be familiar with who you are.

“From there, their recommendations or chatter can appear like grassroots word of mouth endorsements and have a longer effect,” she said.