Faulty assumptions and flawed advice are complicating Washington’s approach to Beijing, says former SCMP editor-in-chief Wang Xiangwei.

US President Donald Trump speaks during a swearing-in ceremony for the new US ambassador to China, former US Senator David Perdue, at the White House in Washington, DC, US, May 7, 2025. (Photo: Reuters/Leah Millis/File Photo)

New: You can now listen to articles.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

HONG KONG: United States President Donald Trump believes China is on the brink of collapse. He’s said as much repeatedly, claiming that Beijing is “getting killed” by his tariffs, that Chinese factories are closing and that unemployment is soaring.

As someone who’s written about China’s relations with the US for more than 30 years, I find it fascinating to observe how Mr Trump's bluster and bluffing tactics have failed to pressure China into submission in their trade war.

More critically, his bullying approach seems to reflect a significant misunderstanding of China and its leadership, which could have negative implications for future bilateral discussions. This raises the question of whether Mr Trump is receiving sound advice regarding his strategy toward China.

Some might argue that in his aggressive pursuit of an America First agenda, it is Mr Trump’s prerogative to disregard how the rest of the world, including China, perceives his actions. While this may hold some truth, a review of Mr Trump’s public speeches and social media posts reveals a profound misapprehension of China and its intentions.

WHAT HOLDS UP, AND WHAT DOESN’T

For instance, as soon as Beijing began its tit-for-tat retaliation against US tariff increases on Chinese imports in early April, Mr Trump took to his Truth Social platform to declare: “China played it wrong, they panicked – the one thing they can’t afford to do,” emphasising every word in capital letters.

As China stood firm and vowed to “fight till the end”, Mr Trump claimed in a May interview that “China is getting killed right now” and “They’re getting absolutely destroyed.” He asserted that China’s economy “is collapsing”.

His claims are greatly exaggerated.

Official data indicate that while China’s exports did slow down in May, it still grew 4.8 per cent year-on-year, despite a 34.5 per cent drop in shipments to the US. And although industrial output growth eased from 6.1 per cent in April to 5.8 per cent in May, it remains robust, and retail sales - a key gauge of consumer demand - surged by 6.4 per cent in May, exceeding expectations.

While China may be facing deflationary pressures, its economy is far from the collapse that Mr Trump imagines. Overall, he has drastically underestimated Beijing's political strategy and its willingness to endure short-term economic challenges.

DONALD TRUMP’S CHINA INTEL

Last month, Mr Trump reportedly downsized the National Security Council - which advises the president on foreign policy and national security matters - letting go of most of the China team, seemingly as part of a broader effort to reduce the influence of those who might oppose his America First agenda.

This raises another important question: Where is he obtaining his information about China?

Mr Trump's known affinity for Fox News is well-documented. He’s appointed more than a dozen former Fox News hosts, journalists and commentators to senior positions during his second term in office. These include Pete Hegseth as Defense Secretary, former Fox pundit and US Representative Tulsi Gabbard as Director of National Intelligence, and former Fox Business host Sean Duffy as Transportation Secretary.

Meanwhile, figures like Gordon Chang, who infamously predicted in 2001 that China would collapse by 2011 in his book The Coming Collapse of China, has continued to promote his disproven theories in that sphere.

In April, Mr Trump posted a quote on Truth Social by Mr Chang - who has claimed in interviews that Beijing had everything to lose in a tariff war with Mr Trump - calling for more aggressive tariffs on China.

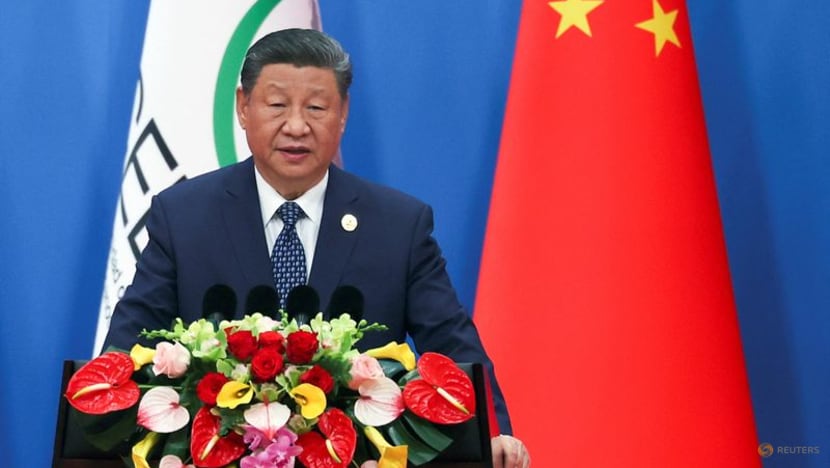

China's President Xi Jinping, pictured here on May 13, 2025, had a long-awaited phone call with US President Donald Trump on Jun 5. (Reuters/Florence Lo/Pool/File Photo)

China's President Xi Jinping, pictured here on May 13, 2025, had a long-awaited phone call with US President Donald Trump on Jun 5. (Reuters/Florence Lo/Pool/File Photo)

Such misguided perspectives have undoubtedly complicated bilateral discussions between Washington and Beijing. Following talks in Geneva in May, both sides agreed to pause the tariff war and establish a framework for further negotiations. However, this framework quickly fell apart.

From the US perspective, China imposed restrictions on critical mineral exports, including rare earth elements. Meanwhile, China viewed the US as continuing to introduce unfavourable measures, such as threatening to revoke Chinese student visas and suspending sales of technology and products used in assembling China’s COMAC C919 aircraft.

The standoff was finally resolved after Chinese President Xi Jinping agreed to speak with Mr Trump on Jun 5. Ironically, just a day earlier, Mr Trump had posted on Truth Social that Mr Xi was “extremely hard to make a deal with”.

This comment again suggests a limited understanding of China’s political dynamics. While Mr Trump has made it clear that he wants to lead negotiations, China prefers that the outcomes be agreed upon beforehand.

A “DONE” DEAL?

The phone call paved the way for discussions in London earlier this month, during which both sides appeared to agree on a new framework to implement the Geneva agreement. Mr Trump claimed in a Truth Social post that a deal had been reached with China, pending final approval from both him and Mr Xi. He seemingly suggested that China had agreed to supply US companies with magnets and rare earth metals, while the US would ease its threats regarding the revocation of Chinese student visas.

However, there is more than meets the eye. It is hard to believe that China would agree to resume rare earth supplies solely in exchange for continued visa issuance for Chinese students. After all, control over rare earths - of which China processes 90 per cent globally - has become a significant leverage point against the US.

It is more plausible that China will continue to push the US to relax restrictions on more advanced chips, even though US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent stated there would be no "quid pro quo" regarding easing curbs on AI chip exports to China in exchange for access to rare earths.

Meanwhile, it is believed that Chinese companies are finding ways to acquire the latest AI chips, as the US restrictions have inadvertently created a booming black market for these supplies. One industry source likens the US restrictions on AI chips to the futility of the Prohibition era in the US.

As one popular meme illustrates, Mr Trump declares, “I hold the cards,” to which Mr Xi replies, “The cards are made in China.”

Wang Xiangwei is a former Editor-In-Chief of South China Morning Post. He now teaches journalism at Hong Kong Baptist University.