Thailand’s Uyghur deportation has generated speculation over whether Bangkok – which has a longstanding and deep relationship with the United States – is drifting into China’s sphere of influence, says former foreign correspondent Nirmal Ghosh.

File photo. This photo provided by Thailand's daily web newspaper Prachatai shows a vehicle with a load of unidentified passengers in Bangkok, Thailand, on Feb 27, 2025. (Photo: Nuttaphol Meksobhon/Prachatai via AP)

New: You can now listen to articles.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

BANGKOK: It was “probably true, but what a silly thing to admit”, the famously blunt Bilahari Kausikan, former permanent secretary of Singapore’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, remarked in a post on Facebook this month.

He was reacting to a remark by Thailand's vice minister for foreign affairs, Russ Jalichandra, who had that said Thailand’s decision to deport 40 Uyghurs to China was to avert potential fallout with China. “Thailand could face retaliation from China that would impact the livelihoods of many Thais,” Mr Jalichandra was cited as saying.

The Uyghurs deported in February were part of a group of 300 who fled China and were arrested in Thailand in 2014. Some had previously been sent back to China and others to Türkiye, while the others remained in Thai custody for over a decade.

Human rights groups have long accused China of widespread abuses against the mainly Muslim ethnic Uyghurs of Xinjiang – which Beijing denies.

The international reaction against Thailand was swift. Volker Türk, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, said the return of the Uyghurs “violates the principle of non-refoulement for which there is a complete prohibition in cases where there is a real risk of torture, ill-treatment, or other irreparable harm upon their return”.

The US issued a travel warning, citing retaliatory attacks in the past from similar deportations. In August 2015, a powerful bomb blast at the storied Erawan shrine in downtown Bangkok killed 20 people and injured 163, and was later traced by Thai police to Uyghurs likely retaliating for Thailand’s deportation of 109 Uyghurs to China the previous month.

Japan’s Embassy issued a similar warning; Japanese nationals were among the dead in the 2015 attack. Australia’s Foreign Minister Penny Wong said the Australian government “strongly disagrees with the decision of the Thai government”.

On Mar 14, the US placed visa restrictions on current and former Thai officials “responsible for, or complicit in, the forced return” of the Uyghurs.

CHINESE ASSURANCES

Thai officials have defended the deportation, saying China had guaranteed verbally and in writing that the Uyghurs would be treated humanely. Follow-up visits to monitor that were agreed as well; the first – amid allegations that it was carefully stage managed - took place last week (Mar 17 to 20) featuring Thailand’s Deputy Prime Minister Phumtham Wechayachai and Justice Minister Tawee Sodsong accompanied by military officials and selected Thai media.

Concerns, however, have been raised about the visit. Journalists on the trip were escorted by security personnel who reportedly requested to vet images being transmitted to Thailand, said Pranot Vilapasuwan, news director at the Thai language daily Thairath, on Facebook. The journalists were also vetted by Thai authorities prior to the trip.

The Thai delegation met or had video calls with only a handful of the Uyghur deportees and concluded that they were happy to be back and living a normal life.

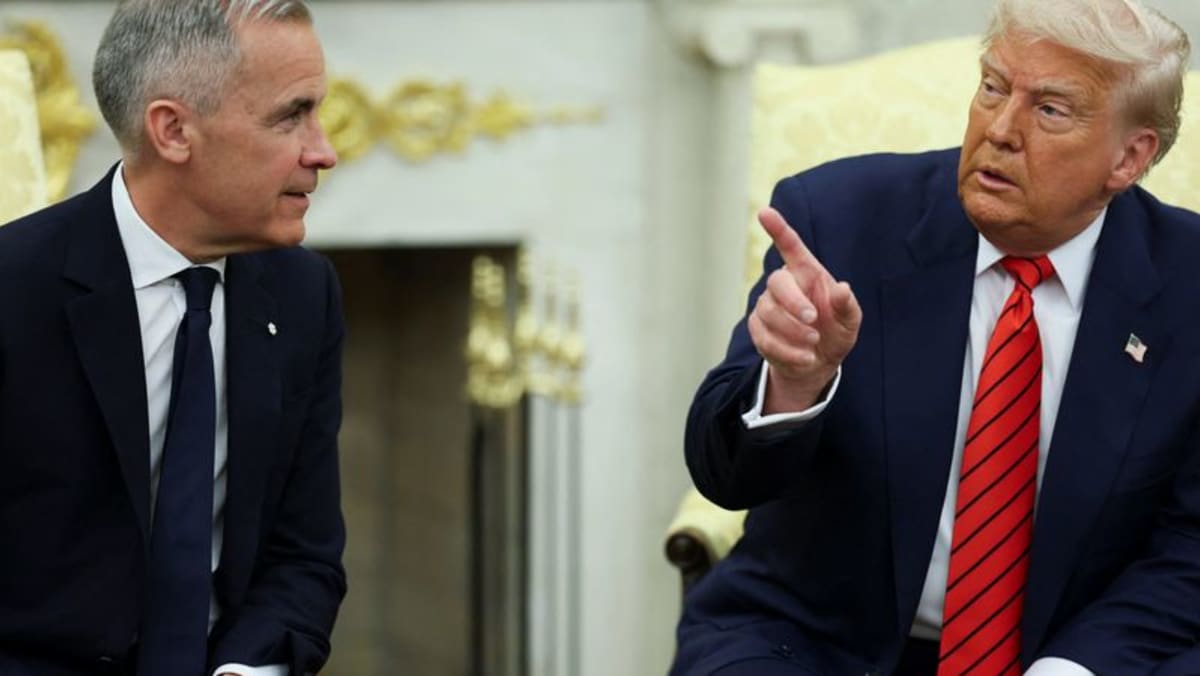

The episode has generated speculation as to whether Thailand – which has a longstanding and deep relationship with the United States – is drifting into China’s sphere of influence.

“Thai people understand that Thailand is a small nation in a crucial geographic position and needs to be on everybody’s side,” Mr Sunai Phasuk, senior researcher at Human Rights Watch, told me.

“But there is also an impression that China takes advantage of Thailand, and that has become more pronounced,” he added. “They (the current Thai government) should be more careful.”

COSYING UP TO CHINA

Certainly, Thailand’s relationship with the United States remains close. Washington DC counts Bangkok as its oldest ally in Asia and Thailand hosts the annual Cobra Gold military exercise – the largest joint multilateral military exercise of its kind in the Asia Pacific.

But Thailand’s ties with China are traditional, and also lucrative. China is Thailand’s biggest source of tourists and among its top three foreign investors.

In January, Thailand’s Board of Investment said it expected at least US$28.8 billion worth of investment applications this year, following a 10-year high in 2024. Part of the reason for the optimism: Companies relocating production from China to escape US tariffs.

On Mar 13, Thailand approved a more than US$1 billion investment by a unit of China’s Sunwoda Electronic to build electric vehicle battery manufacturing facilities in the Eastern Economic Corridor area. On Mar 17, Thailand approved a US$2 billion investment by China’s Beijing Haoyang Cloud Data Technology to build a 300MW data centre.

File photo. Thailand's Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra (left) shakes hands with Chinese President Xi Jinping (right) in Beijing, China, on Feb 6, 2025. (Photo: AP via Thailand's Government Spokesman Office)

File photo. Thailand's Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra (left) shakes hands with Chinese President Xi Jinping (right) in Beijing, China, on Feb 6, 2025. (Photo: AP via Thailand's Government Spokesman Office)

Thailand has for decades been adept at navigating between great powers. Its foreign policy has been likened to “bamboo diplomacy” – bending with the wind but not breaking.

Mr Sihasak Phuangketkeow, a former permanent secretary and vice minister for foreign affairs in the previous Thai government, told me: “We need the Chinese, but we also have to stand up to China. Thailand should show leadership in Southeast Asia, we cannot show that we are subject to their pressure.”

He added: “We also need the US to maintain the balance of power, but it’s certainly not in our interest to align with the US against China.”

Dr Pavin Chachavalpongpun, professor at Kyoto University’s Centre for Southeast Asian Studies, does not see a dramatic shift towards China. “I don’t think there has been any major shift in Thai-Chinese relations. This has been the kind of relationship we’ve had for quite some time,” he said.

He noted how former Thai prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra, whose daughter and current Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra is widely seen as his proxy, had visited his family’s ancestral tombs in China.

Thaksin and his sister Yingluck, who was also prime minister before being unseated in the 2014 coup, are fourth-generation Hakka Chinese immigrants with ancestral roots in Guangdong, China. In 2001 Thaksin visited the ancestral village; in 2014 he again visited the place together with his sister.

Yet while Thailand has been good at balancing the big powers, these are testing times – and the deportation of the Uyghurs reflects poor diplomacy on Thailand’s part. “They could have done the same thing (deport the Uyghurs) - but more intelligently,” said Dr Pavin.

Separately, when asked whether it was valid to infer that the Uyghur episode suggested Thailand was tilting toward - or even deferring to – China, a senior Thai official pushed back, calling the premise flawed.

“It’s not a yes or no answer,” the official said. “It’s about accommodation.”

Nirmal Ghosh is a former foreign correspondent and independent author and writer based in Thailand and Singapore.

.png?itok=erLSagvf)