Burnout is not a sudden event, but a slow and gradual process that unfolds progressively over five phases, just like an increasingly burnt piece of toast. (image: iStock/olm26250)

New: You can now listen to articles.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: I was standing in my kitchen, cooking dinner, when my vision suddenly blurred. The porcelain plate in my hand slipped and shattered at my feet. That’s when I knew something had gone very wrong.

In Singapore, we wear our hustle like a badge of honour. Long hours, marathon meetings and late-night emails are sometimes seen as signs of dedication and commitment.

But the line between dedication and depletion is dangerously thin. Multiple studies have found that Singapore has some of the highest burnout rates because of work, with one last year putting the figure at 61 per cent.

Still, many of us believe burnout could never happen to us.

I was one of them.

NOPE, NOT ME

I thrived on deadlines. The adrenaline of juggling multiple projects and meetings was thrilling. I was excited to make meaningful contributions.

A senior colleague once warned that I might “burn out in a way that’s not recoverable”. I brushed it off. How could I ever get burnout? I was sleeping well and taking regular breaks.

Like many, I assumed burnout only struck those who did not have as much resilience to cope, or worked under extreme conditions. I thought as long as I had enough rest, I’d be fine.

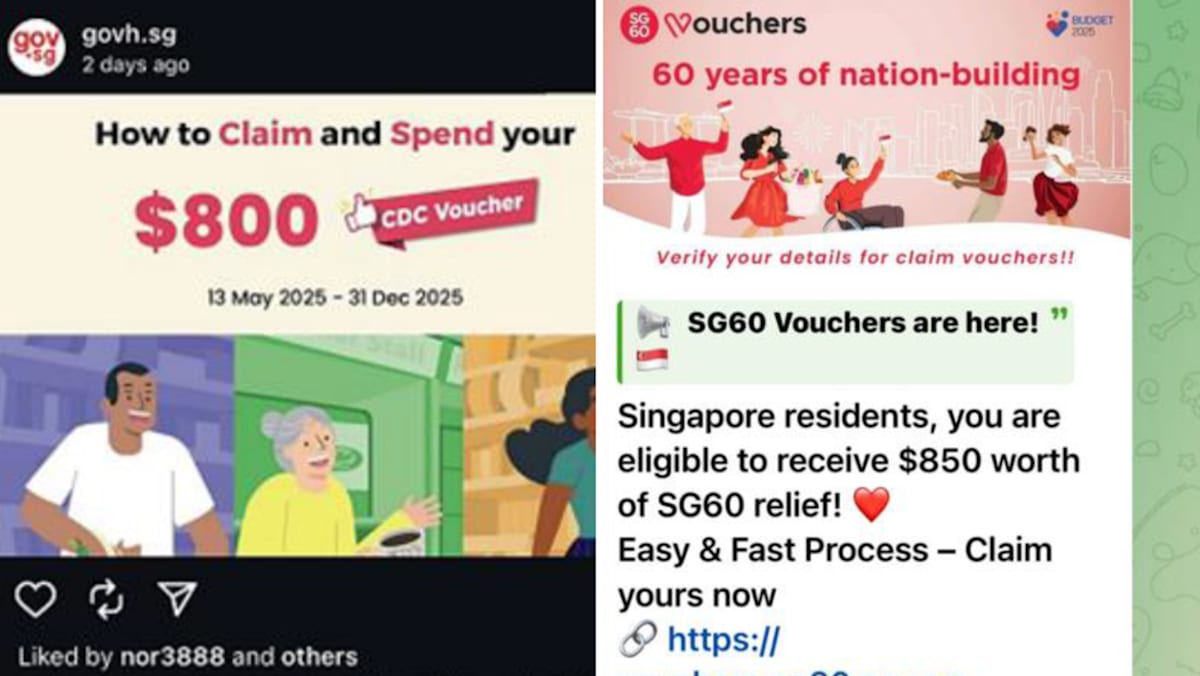

Ironically, days before my breakdown, I attended a mental wellness talk at work. The speaker laid out the idea that burnout is not a sudden event, but a slow and gradual process that unfolds progressively over five phases, just like an increasingly burnt piece of toast.

It starts with the honeymoon phase, where the thrill of something new masks underlying stress. Then comes the balancing act phase, when fatigue creeps in and one becomes easily distracted. The chronic symptoms phase sets in next, marked by constant exhaustion, irritability and even regular physical illness. In the crisis phase, pessimism, cynicism and obsessive work-related frustrations dominate. Finally, in the enmeshment phase, burnout is the default setting, often accompanied by anxiety or depression.

As she spoke, I felt a cold recognition – I experienced them all.

Yet, I remained in denial.

SPIRALLING OUT OF CONTROL

A few days later, a work crisis tipped me over the edge. I felt as if I’d lost control of my own mind. Thoughts spiralled uncontrollably like a broken radio that I couldn’t shut off. Sleep became impossible. The silence of the night only made the noise in my head louder.

Then came the moment in the kitchen: the blurred vision, the shattered plate.

Still convinced that it was something physical, I visited a doctor. He told me I looked terrible and suspected it was burnout. A screening test showed symptoms of moderate depression. I was referred to a psychiatrist, given medical leave and told to rest.

But rest didn’t help. Each passing day felt like a deeper descent into madness. Work messages on my phone triggered panic attacks. I couldn’t function.

On the outside, I looked fine, just tired. Inside, I was falling apart.

Some people thought I simply lacked motivation, that all I needed was rest or willpower. Their well-meaning comments only deepened the loneliness.

THE LONG ROAD TO RECOVERY

Recovery was slow and painful, but thankfully, possible.

Professional support was my first lifeline. My counsellor taught me how to navigate the storm inside my head, how to recognise stressors and how to manage them better. My psychiatrist prescribed anti-depressants to quieten the constant mental noise.

Support also came from a compassionate colleague. Despite his busy schedule, he made time to talk and offered encouragement. Even a simple, “You look good today”, had the surprising power to uplift me. He encouraged me to focus on projects that brought me joy.

Months later, I transitioned into a new role, one that aligned more closely with my values and gave me a renewed sense of purpose.

Seven months have passed since the plate shattered. I’m no longer the energetic person I once was. I tire easily. As I begin weaning off the anti-depressants, the heightened anxieties and unstoppable noise in my head have returned – an unpleasant new normal I’m learning to accept.

WHAT BURNOUT TOOK FROM ME– AND WHAT IT TAUGHT ME

My experience taught me something I didn’t understand before, that burnout isn’t just about working too hard or too long.

Burnout insidiously happens when we work in ways that betray our own values and needs. It begins with making small compromises, like suppressing our instincts, silencing our needs or bending our values for others. We give excuses for making these exceptions, by telling ourselves that it’s only temporary, necessary, or that it’s part of the job.

With each compromise, we lose a piece of ourselves.

Eventually, those compromises become the norm. We lose joy, energy and purpose – and finally, we lose ourselves.

I used to think resilience meant pushing through at all costs, no matter how tough the situation may be, as it was important to put our responsibilities and duties to others over self.

Now, I know better.

True resilience includes rest. It includes knowing when something is not good for our well-being and giving ourselves permission to walk away.

Self-care and happiness aren’t rewards we earn after the grind. Rather, they are the fuel that keeps us going.

A BETTER WAY FORWARD

From my experience, I realised that burnout recovery – and prevention – isn’t something a weekend getaway or a mindfulness app can fix on its own.

What helped me the most were gradual, deliberate changes to both my environment and how I related to my work.

I learnt to set firmer boundaries, not just physically but digitally too. It’s surprisingly difficult to break bad habits like checking work messages, especially when the pings and alerts are constantly clamouring for my attention. Disabling all notifications on my phone helped me reclaim a strong sense of control I felt I had lost in a long time.

I also started reassessing the responsibilities I had taken on. Some were rooted in a sense of duty, others in the fear of disappointing people. But I began to notice that not all the pressure came from others. Sometimes, it was the voice of my own inner critic pushing me the hardest. Recognising this was the first step towards being kinder to myself.

I don’t have all the answers, but I believe we thrive better when we create supportive environments that enable us to make authentic choices for ourselves. This makes it conducive for us to develop healthier, more sustainable working habits.

We may not have the power to change everything, but we have the power in choosing how we respond to our stresses and how we protect ourselves.

Jonathan Sim is Lecturer of AI & Philosophy with the NUS Learning & Development Academy and Fellow of the NUS Teaching Academy.