The disruption unleashed by Trump’s tariffs will not stop at the stock market; it will reverberate through factories, ports and storefronts worldwide, say professors Angela Huyue Zhang and S Alex Yang.

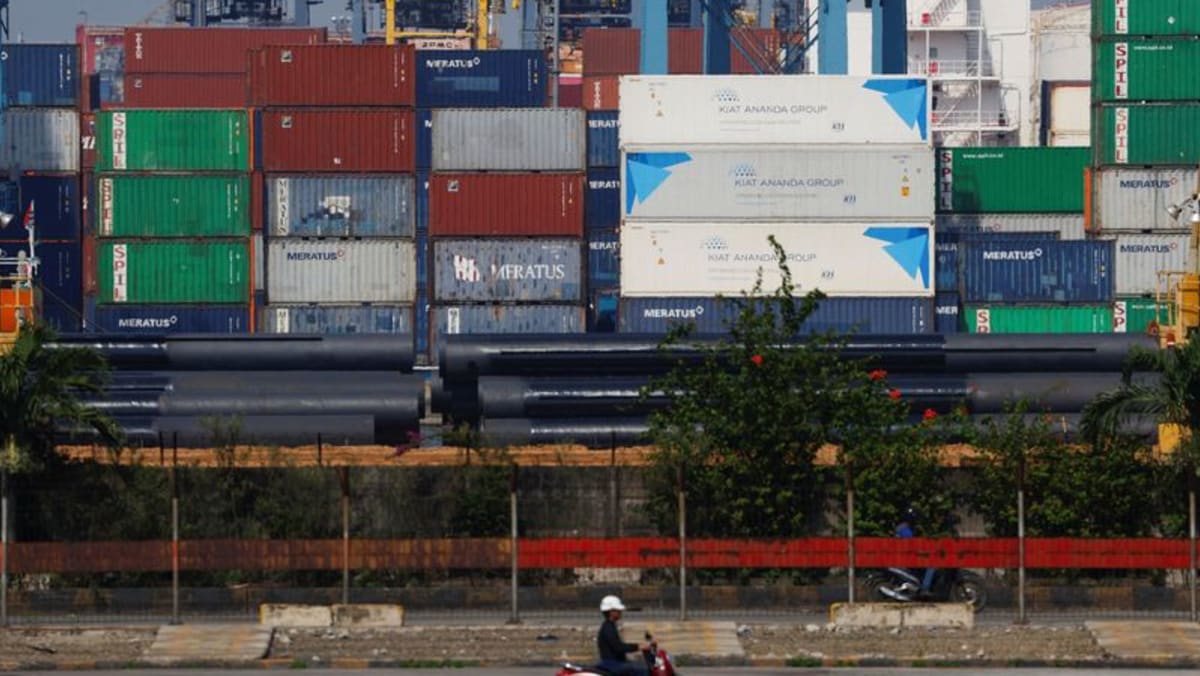

Shipping containers at the port of Oakland, California as trade tensions continue over US tariffs with China, May 12, 2025. REUTERS/Carlos Barria

LONDON: The White House announced on Sunday (May 11) that the United States and China will temporarily suspend or lift the import tariffs they imposed on each other in April, pending further negotiations on a trade agreement. But while the announcement offers long-awaited relief to businesses and has boosted market confidence, investors would be wise to curb their enthusiasm.

Taking cues from his background in business, Trump uses tariffs as a bargaining chip, seemingly convinced that aggressive escalation will force US trading partners to offer significant concessions and enable him to declare a major political victory. But negotiating a trade agreement is not the same as striking a real estate deal. The process is slower, messier and far more consequential.

This is particularly true when the US is negotiating with China, which has both a huge economy (and thus substantial leverage) and a strong interest in withholding concessions, because yielding to Trump’s demands could undermine national pride and trigger a domestic backlash.

And while Trump has a record of declaring dubious victories, it would be difficult for him to claim success in his trade war with China if he simply backed down. As a Chinese saying goes, once you are riding a tiger, it is difficult to get off.

TRADE AGREEMENT DIFFICULTIES

A trade agreement between the world’s two largest economies would be difficult to draft and nearly impossible to enforce. We saw this clearly in 2018 and 2019. Although the US and China reached an agreement in principle in April 2019, negotiations ultimately fell apart, owing to differences over the specificity of the terms.

Whereas the US demanded a rigid, 150-page contract detailing legal reforms to be enacted through China’s national legislature, China sought a more flexible, principles-based framework that could be implemented through less visible regulatory measures.

Then there is the enforcement challenge. When the US and China signed their “phase one” trade deal in January 2020, Trump declared it a historic victory, touting China’s commitment to increase purchases of US goods and services by US$200 billion over two years, along with other concessions.

But unlike typical trade agreements, the deal contained no neutral third-party enforcement mechanism. Nor was it self-enforcing, with both parties viewing compliance as more beneficial than defection. So, when China failed to meet its purchase targets, the US – then led by President Joe Biden – had little recourse.

Today, even if tariffs are to be lifted in the short term, China has little reason to believe that the US will honour its commitments or pursue meaningful enforcement, especially given the tremendous mistrust that Trump has sowed. Ultimately, any trade deal that the US and China negotiate is likely to be fragile, limited in scope, and vulnerable to collapse. Businesses and investors should thus be prepared for continued disruptions across global supply chains.

LASTING HARM TO GLOBAL SUPPLY CHAINS

In fact, Trump’s trade war has already done lasting harm to global supply chains. Retailers have been scrambling to cancel orders, manufacturers and distributors have rushed to reroute and stockpile inventories, and businesses have been operating in a climate of heightened uncertainty. It is now clearer than ever that small and short-lived fluctuations can cause disproportionate and long-lasting disruptions, or what supply-chain experts call the “bullwhip effect”.

This phenomenon is reflected in the outlook for Christmas this year. If a made-in-China toy is to reach store shelves in the US before the holidays, the production process must begin as early as March, when toy companies finalise product designs and place orders.

Manufacturing typically starts in April, with goods shipping from Chinese factories by July, so that they arrive in the US before fall distribution. Retailers depend on this long but tightly choreographed timeline to meet seasonal demand.

Fluctuating tariffs disrupt every stage of this process. Faced with unpredictable costs, retailers hesitate to place orders, delaying production and shipment. Suppliers then reconfigure production lines to take advantage of any new opportunities, meaning that the reversal of tariffs alone may not be enough to get production back on track.

So, even if the elimination of tariffs revives demand, the supply shortage would persist, driving prices higher – a possibility that Trump dismissively acknowledged at a recent cabinet meeting.

Container cranes sit idle at the port of the port of New York and New Jersey, May 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Container cranes sit idle at the port of the port of New York and New Jersey, May 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

DISRUPTIONS CAUSED BY UNPREDICTABILITY

Making matters worse, higher prices could send the wrong demand signal to suppliers, aggravating the long-term problem of oversupply that tariffs are meant to tackle. This cycle of oscillation – a hallmark of the bullwhip effect – creates persistent instability. After all, it’s not the average that kills you; it’s the volatility.

We saw a version of this dynamic during the COVID-19 pandemic, when sudden shutdowns triggered cascading shortages and gluts across global supply chains, with effects that were felt for years. The difference now is that the turmoil is not the result of a natural disaster or public-health crisis; it is the product of a deliberate policy.

Unpredictability may have worked for Trump in his personal business dealings, but when applied to global commerce, it generates tremendous chaos, as supply chains thrive on transparency and certainty, not bluffs and sudden policy reversals.

The disruption unleashed by Trump’s tariffs will not stop at the stock market; it will reverberate through factories, ports and storefronts worldwide. Investors, policymakers and consumers have yet to reckon fully with the consequences of Trump’s actions.

Angela Huyue Zhang is Professor of Law at the University of Southern California. S Alex Yang is Professor of Management Science and Operations at London Business School. This commentary first appeared on Project Syndicate.

.png?itok=erLSagvf)