SINGAPORE: China’s export engines are fired up with Southeast Asia firmly in the front view, a focus which analysts say is only set to heighten as Chinese products lose their lustre in the West amid intensifying geopolitical tensions and a Trump 2.0 presidency in the United States.

This means the perks and pitfalls for the region will become more pronounced, driving home the growing need for countries to coordinate a response to Beijing as they work to balance the scales, observers note.

On the one hand, consumers in Southeast Asian nations gain as they enjoy the variety and relative affordability of Chinese goods. But on the other hand, local industries face an increasingly fraught landscape.

“Struggling to match these low prices, local businesses are witnessing eroding profit margins, plant closures, and widespread job losses,” noted Doris Liew, an economist and assistant research manager at the Malaysian think tank the Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs (IDEAS).

“Southeast Asia is grappling with the ripple effects of China's export glut, a challenge that extends beyond the region.”

As some Southeast Asian states mull countermeasures such as anti-dumping tariffs, analysts say the crux is whether they can work together to navigate the landscape, especially considering their varying stages of development and differing needs.

“The reality is that the consequences are wildly different for individual industries … a single cross-region or even cross-industry outcome is therefore unlikely,” Diana Choyleva, chief economist at Enodo Economics, told CNA.

FIRING UP THE EXPORT ENGINES

China’s export engine has been firing on multiple cylinders as its domestic economy struggles with a cooling property sector and tepid consumer demand. Exports make up around 20 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP).

Exports in 2024 grew 7.1 per cent year-on-year to 25.45 trillion yuan (US$3.47 trillion), exceeding 25 trillion yuan for the first time, according to China customs data released on Monday (Jan 13).

“China consolidated its position as the world's largest trading nation in goods,” said Wang Lingjun, deputy head of the General Administration of Customs, at a press conference on Monday.

Overproduction by Chinese manufacturers, coupled with challenges to the domestic economy, has resulted in a surplus of goods that run the gamut from low-cost to premium products, Liew observed.

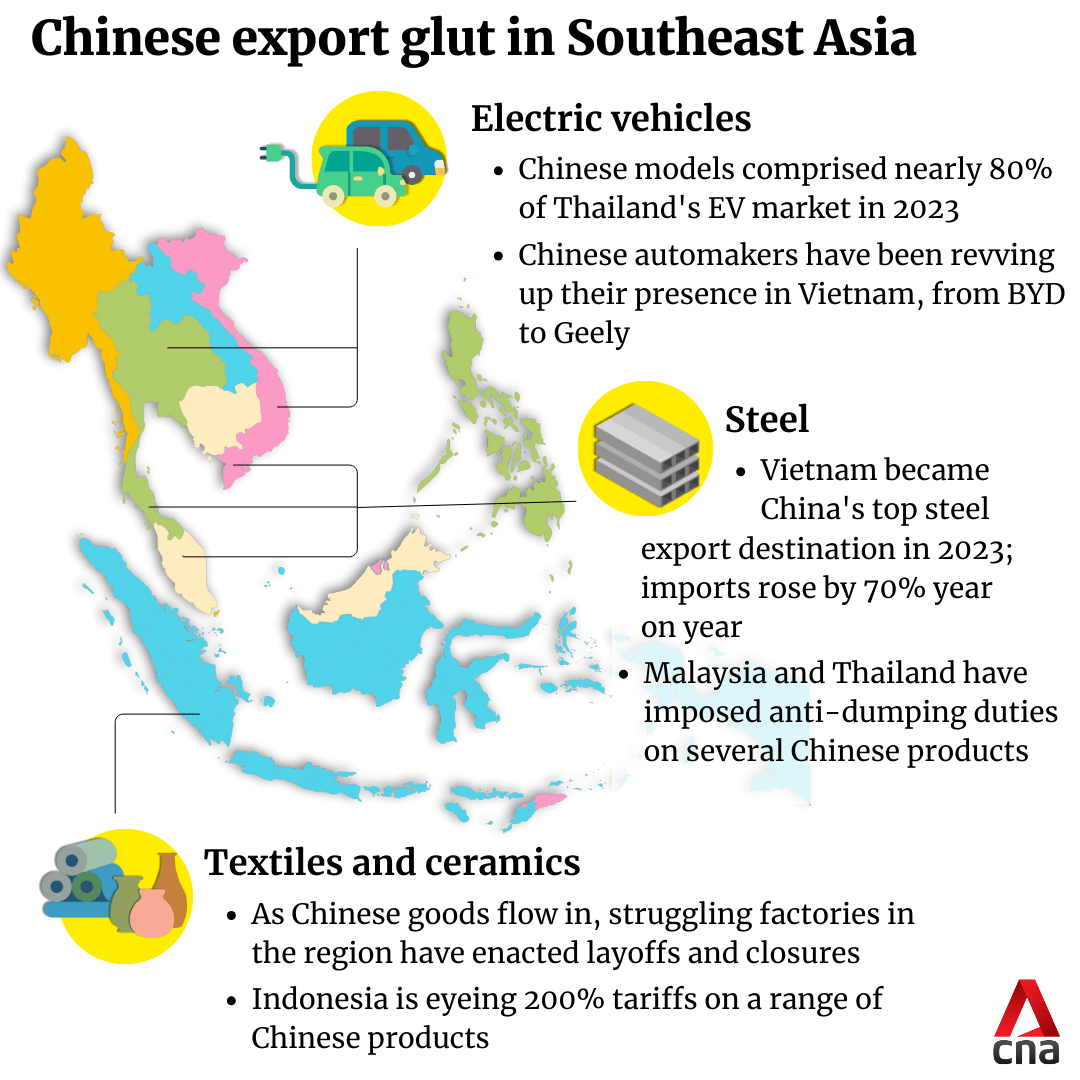

While small-ticket items like textiles and clothing continue to be shipped abroad, big-ticket products are being revved up. The combined export value of China’s so-called “new trio” - electric vehicles, lithium batteries and solar panels reached 1 trillion yuan last year, a 900 per cent increase from a decade ago.

“To alleviate this glut, Chinese manufacturers are exporting these products - often at prices below production cost - thereby distorting global markets,” Liew told CNA, noting that China’s industrial policies have contributed to this strategy.

Analysts say many of these goods are increasingly finding their way to Southeast Asia as Sino-West tensions intensify, and Western nations take growing countermeasures.

“A more fractious trade relationship between the US and China could also fan trade tensions within Asia. With demand from the US and Europe waning, China has already pivoted towards Asian markets,” Priyanka Kishore, director and principal economist at Asia Decoded, told CNA.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is the third-largest economy in Asia, and with the China-ASEAN Free Trade Area, Beijing has found fewer barriers to exporting its goods.

The proportion of Chinese exports going to ASEAN member states has climbed from 6.9 per cent at the start of the century to around 16 per cent today. Chinese customs data showed that ASEAN emerged as China's largest export market in 2023, with an annual value reaching US$523.7 billion.

ASEAN leaders on stage for a photo session during the 27th ASEAN -China Summit in Vientiane, Laos, Oct 10, 2024. ASEAN is China's top trading partner, and Chinese shipments to the bloc grew by 12 per cent in 2024. (Photo: AP/Dita Alangkara)

ASEAN leaders on stage for a photo session during the 27th ASEAN -China Summit in Vientiane, Laos, Oct 10, 2024. ASEAN is China's top trading partner, and Chinese shipments to the bloc grew by 12 per cent in 2024. (Photo: AP/Dita Alangkara)

THE PERKS AND PITFALLS

The increasing flow of Chinese goods into Southeast Asia has been a boon to consumers.

Such products are often cheaper compared to their ASEAN equivalents, offering a more affordable option for shoppers, particularly for low-income households.

Certain high-tech offerings like electric vehicles are also generally well-regarded as being value for money, challenging past perceptions that made-in-China goods are of suspect quality and workmanship.

But the influx has also proven a bane for local businesses, hitting livelihoods, as they struggle to match the low prices dangled by Chinese rivals.

This competitive imbalance has led to a concerning decline in production capacity across the region, said Liew from IDEAS.

In Indonesia, textile goods and ceramics have been the primary casualties, said Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat, director of the China-Indonesia Desk at the Jakarta-based research institute the Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS).

“The influx of Chinese goods into Indonesia is destroying the local businesses,” he told CNA. Last year, Indonesia’s textile, garment and footwear industry reported job losses in excess of 50,000 due to factory closures.

Meanwhile, Thailand witnessed around 2,000 factory closures between July 2023 and June 2024, roiling its manufacturing sector that contributes nearly a quarter of the country’s GDP. More than 50,000 jobs were lost.

“The surge of cheap Chinese imports has triggered domestic protests in many ASEAN economies and verbal pushback from the governments,” said Kishore.

“Faced with an even more hostile trading environment in the West, the mainland will likely direct more of its excess supply towards its neighbours, leading to increased trade frictions.”

A number of Southeast Asian nations have already taken action.

Vietnam launched an anti-dumping investigation in August 2024 on hot-rolled coil products from China and India, while extending duties on aluminium products from China for five more years, with tax rates ranging from 2.85 per cent to 35.58 per cent.

Additionally, Vietnam suspended the operations of Chinese e-commerce giant Temu in December 2024 after it missed a government deadline to register the company. The move came after authorities had raised concerns about the authenticity of Temu’s extremely cheap products and their impact on Vietnamese manufacturers.

Thailand meanwhile has identified 58 products, including steel and furniture, as targets for anti-circumvention duties, and proposed imposing a 30.9 per cent tariff on Chinese hot-rolled steel.

To manage low-cost imports, Thailand also introduced a 7 per cent value-added tax on goods below 1,500 baht (US$40) in July 2024. By December 2024, this move had led to a 20 per cent reduction in low-quality imports, mostly from China, according to Thai officials.

Over in Indonesia, trade minister Zulkifli Hasan said in July 2024 that the government would look at imposing duties of up to 200 per cent on various Chinese imports, such as textiles, ceramics, and other goods, to protect its domestic industries.

Crowds at Tanah Abang market in Jakarta, Indonesia, a major hub for textile trade in the country. Indonesia is eyeing 200% tariffs on a range of Chinese products including textiles and ceramics. (Photo: AP/Achmad Ibrahim)

Crowds at Tanah Abang market in Jakarta, Indonesia, a major hub for textile trade in the country. Indonesia is eyeing 200% tariffs on a range of Chinese products including textiles and ceramics. (Photo: AP/Achmad Ibrahim)

Even as counteractions are taken, analysts do not expect any major economic confrontation between China and Southeast Asian nations.

Kishore highlighted that China is a key supplier of certain goods like machinery and chemicals to the rest of the region. “Imposing substantial taxes on these would only harm domestic manufacturers,” she pointed out.

“It would serve the region’s interests better to take a balanced approach and resolve issues through dialogue with China rather than trade retaliation.”

Echoing this, Choyleva from Enodo Economics noted that Southeast Asia is a “target region” due to factors like its geographical closeness, “decent infrastructure” as well as an existing industrial base, enabling companies to move the finishing of products to the region with “relative ease”.

“Much of this activity (Chinese exports to Southeast Asia) is not part of a coordinated strategy by Beijing … but rather the initiative of individual, often private, enterprises themselves looking to find outlets for their own production,” she told CNA.

Chinese officials have not directly addressed reports of an export glut in Southeast Asia. However, Beijing has consistently refuted allegations of industrial overcapacity, particularly in sectors such as electric vehicles, lithium batteries and solar panels.

They argue that the claims are unfounded and serve as pretexts for economic protectionism, aimed at suppressing China's industrial development.

RIDING ON THE REGIONAL RESPONSE

Amid a growing Chinese export wave, analysts say how matters pan out in the region depends heavily on the collective response of ASEAN member states.

“(Economies in the region) are likely to continue pushing the current line of persuading Chinese companies to invest more in their economies and limit exports,” said Kishore, noting that efforts would be particularly pronounced in industries like EV manufacturing that could help the region move up the technological ladder.

Liew from IDEAS deems it unlikely that Southeast Asia will become a “dumping ground” for China’s excess production.

Southeast Asia’s population of 675 million, while substantial, lacks the purchasing power to absorb large quantities of surplus goods, she noted. Furthermore, “periodic anti-dumping controls” help keep market distortions in check.

If managed carefully, deeper economic integration with China could bring infrastructure benefits, advanced technology and job creation, said Choyleva from Enodo Economics.

That being said, the impact will likely be “very unevenly distributed” as ASEAN countries are at varying levels of progress, she cautioned.

THE INDONESIAN CASE: MIXED BLESSINGS

Indonesia exemplifies the complex relationship between cheap Chinese imports and local industry pushback.

In 2022, trade between China and Indonesia accounted for approximately 25% of Indonesia’s total trade. Chinese imports represented 28.52% of Indonesia's total imports that year, retaining Beijing as Indonesia’s largest import source for 13 consecutive years.

Trade between the two nations has “grown exponentially” in recent years, said Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat, director of the China-Indonesia Desk at the Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS).

But Rakhmat highlighted an imbalance, noting that China appears to “benefit more” from the relationship. Referencing Jakarta’s proposed tariffs on certain Chinese textiles, Rakhmat described them as "reactionary," warning of potential "retaliatory measures" from Beijing.

Yet cheap imports find an eager market among Indonesia’s middle class.

“The cheapness of goods, especially in the context of Indonesia … it’s very attractive for them,” Rakhmat said.

Similarly, consumers benefit from competitively-priced Chinese smartphones.

“Chinese phones are dominating the phone market in Indonesia … by that, Indonesians now are well connected,” noted Rakhmat, further pointing out that China has contributed much to Indonesia’s network infrastructure network.

Balancing these gains with industrial competitiveness is a constant challenge. Rakhmat suggests “diversifying more with countries that can be considered as (Indonesia’s) non-traditional partners,” such as the Middle East and Latin America, while “strengthening domestic industry” to avoid over-reliance on one supplier.

Collapse Expand

Coordination among the ASEAN economies in responding to China is also a “long way off”, added Choyleva, who highlighted how Thailand actually negotiated for tariff-free access for Chinese EVs before the domestic price war began to undercut local manufacturers.

“Political differences between ASEAN member states will also inhibit future coordination,” she said.

Liew from IDEAS believes a more coordinated and proactive regional response is required.

“Policymakers must focus on strengthening domestic industries through innovation and investment while implementing targeted trade policies to maintain a level playing field,” she said.

“The region’s ability to adapt will determine whether it emerges as a victim of global oversupply or a resilient player in the global market.”

.png?itok=erLSagvf)